By organ

By program

UNet

Policy

Patient safety

Improvement

Learn

Perspectives

COVID

All

Top stories

OPTN Task Force sets goal of achieving 60K transplants by 2026

The OPTN Expeditious Task Force embarks on ambitious project to save more lives, increase efficiency

Public Comment open from Jan. 23 through March 19, 2024

The OPTN is offering 11 items for review, including one proposal, one guidance document, two request for feedback, three data collections, and four policy proposals.

2023: a year of more lives saved

Celebrating memories made and milestones reached, thanks to the gift of life.

OPTN Task Force sets goal of achieving 60K transplants by 2026

The OPTN Expeditious Task Force embarks on ambitious project to save more lives, increase efficiency

Public Comment open from Jan. 23 through March 19, 2024

The OPTN is offering 11 items for review, including one proposal, one guidance document, two request for feedback, three data collections, and four policy proposals.

2023: a year of more lives saved

Celebrating memories made and milestones reached, thanks to the gift of life.

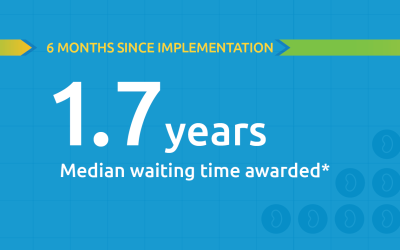

Black kidney candidates are receiving waiting time modifications, helping them get the organs they need

Latest kidney monitoring report shows two new kidney polices are working as intended

Honoring the gift of life: Ceremony marks the National Donor Memorial 20th anniversary

The National Donor Memorial inspires us “to reflect on what it means to be an organ, eye or tissue donor.”

UNOS Travel App wins RVA Tech Award for Innovation

Award recognizes projects that “have a long-term impact,” will serve as “an inspiration for future innovation”

Kidney – Pancreas

Now available: Predictive analytics in desktop DonorNet

These predictions are intended to supplement, not replace, existing data and clinical judgment.

Deceased kidney donors recovered increase six-months post-implementation minimum donor criteria for kidney biopsies

Early data shows a six percent increase of deceased kidney donors recovered in the post-policy era compared to the pre-policy era.

Black kidney candidates are receiving waiting time modifications, helping them get the organs they need

Latest kidney monitoring report shows two new kidney polices are working as intended

Liver – Intestine

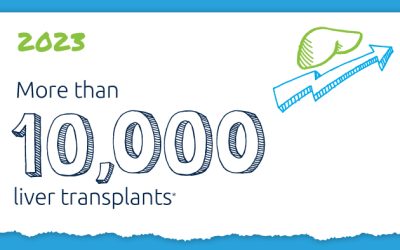

A decade of record increases in liver transplant

10,660 liver transplants, the most ever in a year.

Animated videos describe MELD, PELD formulas

Resource especially designed to inform transplant patients and their caregivers.

Now in effect: Changes to liver-kidney nautical mile threshold

The required share threshold for simultaneous liver-kidney (SLK) allocation has expanded from 250 nautical miles to 500 nautical miles for eligible adult candidates (e.g., Status 1A or MELD of 29 or greater).

Heart – Lung

Lung CAS summary data updated

Information for lung transplant programs on the distribution of scores for all active registrations waiting for lung transplants in the U.S.

Offer Filters now available for lung allocation

Offer Filters adds data-driven, multi-criteria filters to organ offers at a program level so lung transplant programs can filter offers they will not accept and organ procurement organizations (OPOs) can find an accepting candidate more quickly.

Coming soon: Offer Filters for lung allocation

The Offer Filters tool will become available for lung transplant programs in UNetSM on Jan. 31.

VCA

VCA Uterus no longer needs body part selection- effective March 27, 2024

The OPTN’s data collection for vascularized composite allografts (VCAs) in UNet SM

will no longer require body part selection for uterus registered candidates according to VCA committee guidance which specified the body parts (uterus, vagina, cervix).

Extra Vessels included in TIEDI® for VCA

TIEDI® permissions for Vessels Reporting have been added to all 10 VCA organs within Security Administration. These permissions allow designated users either full access or read only access, similar to existing permissions for non-VCA organs. Ensure permissions established before March 6, 2024.

Submit historical VCA collection forms by Feb. 9

New VCA forms available including: TRR and TRF forms that have been updated for the 10 VCA organs. Programs are expected to respond with the new forms completed forms to [email protected] within 90 days of either the date the recipient was removed from the waiting list (TRR), or the date of the six-month or annual anniversary of transplant (TRF) .

Improving the system together

2023: a year of more lives saved

Celebrating memories made and milestones reached, thanks to the gift of life.

Embracing new ideas to increase DCD donation

One year later, three participants share their perspectives on the benefits of the collaborative learning experience.

UNOS research: Insights from the American Transplant Congress

“There is so much intellectual capital assembled at UNOS to study and evaluate the transplant system and find ways to improve through research and analytics.”

UNet

Upcoming change to TransNet user management and access

Site security administrators must set permissions for their TransNet users in Security Administration prior to June 5, 2024.

Coming soon: CPRA >98% form removal for highly sensitized candidates

Transplant hospitals will no longer be required to obtain signatures and update candidate registrations when a candidate’s CPRA is above 98%. There are no changes needed for OPOs.

TransNet organ check-in reporting change effective April 24, 2024

TransNetSM will no longer be available as of April 24, 2024. TransNet users should instead use the Transnet Organ Check-In History Report

Policy changes

Extra Vessels included in TIEDI® for VCA

TIEDI® permissions for Vessels Reporting have been added to all 10 VCA organs within Security Administration. These permissions allow designated users either full access or read only access, similar to existing permissions for non-VCA organs. Ensure permissions established before March 6, 2024.

Pre-implementation notice: New pre-transplant performance metric

A new risk-adjusted performance monitoring metric-the pre-transplant mortality rate ratio- will take effect in July 2024.

Latest in reporting positive post procurement donor results

A new permission in Security Administration was added today for transplant programs. Starting Feb. 28, Transplant Programs will be able to view and acknowledge receipt of these notifications from a new dashboard in DonorNet. The dashboard will be visible only to hospital users who have this new permission to acknowledge these notifications.

Policy monitoring

Deceased kidney donors recovered increase six-months post-implementation minimum donor criteria for kidney biopsies

Early data shows a six percent increase of deceased kidney donors recovered in the post-policy era compared to the pre-policy era.

Black kidney candidates are receiving waiting time modifications, helping them get the organs they need

Latest kidney monitoring report shows two new kidney polices are working as intended

Lung transplant rates continue to increase six months post implementation of new lung policy

Lung-alone transplants have increased by 11.2 percent.

Learn: Collaborative improvement and educational resources

IN FOCUS

A decade of record increases in liver transplant

10,660 liver transplants, the most ever in a year.

Collaboration

Embracing new ideas to increase DCD donation

One year later, three participants share their perspectives on the benefits of the collaborative learning experience.

Learning Congress planned for OPTN DCD Lung Transplant Collaborative

The Sept. Learning Congress, open to all adult lung programs, will mark the conclusion of eight-month collaborative focused on increasing DCD lung transplantation.

Public Comment open from July 27 through Sept. 19, 2023

The OPTN is offering 14 items for review.

Education

TMF 2024 presenter Jennifer Milton, MBA, BSN, on the OPTN Expeditious Task Force

"Remember to find and celebrate the joy in your work—celebrate the amazing miracle your team creates for others!" Jennifer Milton, MBA, BSN Tell us about your background. While my journey in this field began in 1993 as an organ procurement coordinator, I've spent most...

TMF 2024 presenter Andrea Tietjen, MBA, CPA, on transplant financing

"I have been attending TMF since 2000 and have learned all that I know from attendees and presenters. Transplantation and procurement are dynamic fields, and being in-the-know and learning from others is an invaluable resource. Our learnings have helped us to help our...

![]()

Effective practices

Learn about collaborative improvement projects

Learn about issues impacting patients, donors, donor families, and the national system. Issues and advocacy

Perspectives

Why I volunteer: Valinda Jones, M.S.N., RN, kidney recipient

Board member describes the vital role of volunteers with personal experience in donation and transplantation.

Giving and the Gift of Life: Lindsey C. Jennings, Manager, Philanthropy

There is no greater expression of one’s love for humanity than choosing to become an organ donor.

The liver allocation policy is a success we need to share: Terry Box, M.D., liver recipient

Box’s op-ed highlights how effective policy development is resulting in sicker patients getting liver transplants faster.

Leadership news

OPTN Task Force sets goal of achieving 60K transplants by 2026

The OPTN Expeditious Task Force embarks on ambitious project to save more lives, increase efficiency

OPTN Board approves improvements to reporting of potential patient safety events

Process for reporting enhanced, clarified.

President signs new law increasing competition for OPTN contract

We are committed to working with HRSA, Congress, the wider donation and transplantation community and other stakeholders to ensure the best possible system for patients, donors and their families.

“The dozens of topics presented at TMF shared one thing—our community’s dedication to doing everything we can to constantly improve the system and better serve the patients who rely on us.”

Patient safety

Two guidance documents updated

Resources address VCA donation, geographically endemic infections

OPTN Board approves improvements to reporting of potential patient safety events

Process for reporting enhanced, clarified.

Implementation notice: Required reporting of certain patient safety events now in effect

A new policy is now in effect that requires members to report certain patient safety events within 72 hours of becoming aware of the event.

Transplant hospital

Pre-implementation notice: New pre-transplant performance metric

A new risk-adjusted performance monitoring metric-the pre-transplant mortality rate ratio- will take effect in July 2024.

Two guidance documents updated

Resources address VCA donation, geographically endemic infections

OPTN Board approves improvements to reporting of potential patient safety events

Process for reporting enhanced, clarified.

OPO

Mandatory training and UNet user audit opens Feb. 28, 2024

Beginning Feb. 28, 2024, site security administrators will have four weeks to complete the required audit of their UNet users. Prior to completing the audit, site security administrators must complete the updated training course UNet Security Administration (SYS 150)...

Latest in reporting positive post procurement donor results

A new permission in Security Administration was added today for transplant programs. Starting Feb. 28, Transplant Programs will be able to view and acknowledge receipt of these notifications from a new dashboard in DonorNet. The dashboard will be visible only to hospital users who have this new permission to acknowledge these notifications.

Two guidance documents updated

Resources address VCA donation, geographically endemic infections

Histocompatibility

Coming soon: CPRA >98% form removal for highly sensitized candidates

Transplant hospitals will no longer be required to obtain signatures and update candidate registrations when a candidate’s CPRA is above 98%. There are no changes needed for OPOs.

Member actions required: data collection and VCA implementation

Patient care will not be impacted during this time.

UNOS researchers present studies at 2023 American Transplant Congress

Twenty-two UNOS staff members presented research from 42 studies at the 2023 American Transplant Congress, addressing topics including social determinants of health, offer-acceptance practices, and the impacts of allocation-policy changes.

What happened in public comment? See what the community had to say. View comments

Stories and tributes

Each person touched by organ donation transplant has a unique story. Threads of hope connect them. Find videos, stories and tributes