Insights

Data dashboard monitors equity in access to transplant

UNOS researchers discuss how the OPTN tracks equity through Access to Transplant Score.

Alesha Henderson, Ph.D., UNOS research scientist

Darren Stewart, UNOS principal research scientist

UNOS researchers have developed a data dashboard that provides transparency about how the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network monitors equity in access to transplant. Through an Access to Transplant Score (ATS) and equity monitoring methodology, the Equity in Access to Transplant dashboard allows users to explore how different factors impact how long waitlist candidates have to wait to receive a deceased donor transplant.

But what is equity in access, and how is it measured?

Equity: A guiding principle for policy development

As the highest-performing organ donation and transplant system in the world, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network is focused on equity in access to transplant.

Providing equity is a foundational strategic goal and a guiding principle in the development of policies related to organ allocation and transplantation.

Recent changes to kidney and pancreas allocation are predicted to increase equity for key groups, including women, children, ethnic and racial minorities, and highly-sensitized candidates who are hard to match.

A data dashboard that offers insights into equity

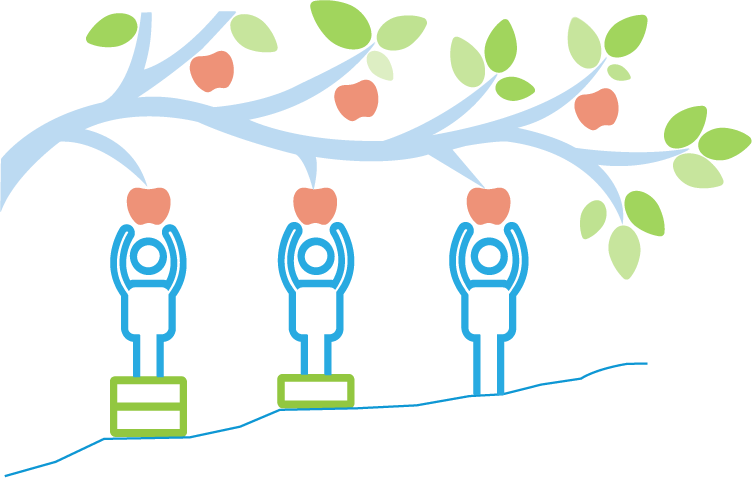

Health equity is the ability for everyone to have the opportunity to be as healthy as possible, no matter their social position.

In order to do their work and increase equity in transplant, the OPTN committee volunteers who develop policy must understand the factors that can impact a waitlist candidate’s access to transplant, including biological or social factors such as blood type, education, gender, race or ethnicity, or whether they live in a rural versus an urban community.

What is an Access to Transplant Score?

The ATS is a single score that indicates a waitlist candidate’s likelihood of receiving a deceased donor transplant in the United States. It involves various individual and community level factors from the NIMHD framework. These factors are not limited to organ transplantation—they contribute to health disparities across multiple health outcomes.

The dashboard developed by UNOS researchers that monitors equity is easily accessed on the OPTN website. Currently it shows data for the heart, lung, liver and kidney allocation systems.

The amount of score variation among waiting list candidates reflects the degree to which the respective organ allocation system is equitable. The goal? To see decreased variation in scores over time—which would mean the system has become more equitable in terms of access to deceased donor transplantation.

A mission centered on equity

UNOS research scientist Alesha Henderson, Ph.D., explains that the ATS follows a framework developed by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, which lays out potential conditions that can influence a person’s health outcomes. Before coming to UNOS, Henderson’s research focused on inequity as it relates to obesity, cancer, oral health, and differential access to healthy foods and safe spaces to engage in physical activity in communities. But her connection with the UNOS mission is also personal—“My grandfather and a great-aunt suffered from kidney disease, and neither one was transplanted. I know about the importance of increasing equity in access to transplant, and I wanted to be a part of that work.”

UNOS principal research scientist Darren Stewart emphasizes that there has been a keen focus on equity in transplant for the past three decades, and that all OPTN policy development involves looking at simulated outcomes to help predict results before changes are made. But the equity data presented in the dashboard is different from the forward-looking simulation modeling used in policy development. Comparing the equity data to looking in the rear-view mirror to see how the system is doing, Stewart says it acts like an early warning system. “These data can alert us to potential disparities in access to transplant and potential detrimental effects on equity,” Stewart says, explaining that these can arise either immediately after a policy implementation or emerge over time. “It means we can be aware of disparities as soon as they happen, and then identify whether something needs to change.” That change might be a policy refinement, communication to the community, or education and awareness.

The future of data dashboards

Stewart is eager to talk about the next generation of OPTN data dashboards. For kidney candidates, the most noteworthy risk-adjusted difference in access to kidney transplant historically been donation service area (DSA). Now that kidney allocation no longer uses DSA to distribute organs, he says that the next iterations of equity dashboards will incorporate center-level variability. “Now that patients are no longer prioritized on the waiting list according to their DSA, there is opportunity to explore what effects can be observed in the transition period, such as whether the DSA effect is changing or not,” he says. “This refined approach will also allow us to take a more granular view of understanding geographic disparities—for example, by teasing out center-specific influences on equity.”

Henderson stresses that while the current version of the dashboard focuses exclusively on equity in access to deceased donor transplants among waitlisted candidates, there are other disparities that are important to explore, asking “Are there inequalities in access to the waiting list in the first place? Are there differences in access to a living donor transplant?” These and other factors are important to recognize and address as the community strives to improve equity in transplant opportunities for everyone in need, and transparency is key to building a fair and equitable system.

View the dashboard

Explore kidney, liver and lung trends in the Equity in Access to Transplant data dashboard.

Do you have questions about the dashboard? Email [email protected].

Trends dashboard

Updated weekly, OPTN metrics dashboard provides comprehensive information about donation and transplant trends.

“My grandfather and a great-aunt suffered from kidney disease, and neither one was transplanted. I know about the importance of increasing equity in access to transplant, and I wanted to be a part of that work.”

Alesha Henderson, Ph.D., UNOS researcher