Improvement

“Roll up your sleeves”: The hard work of increasing organ donors and transplants

Alexandra K. Glazier, President and CEO of New England Donor Services, shares strategies for success

Alexandra K. Glazier, J.D, M.P.H., President and CEO of New England Donor Services, was named Region One Councillor for the OPTN Board of Directors for the new term beginning in July. She is also the incoming Chair of the OPTN Policy Oversight Committee. A past OPO Representative to the OPTN Board (2016-2018), Glazier has also served on the OPTN Data Advisory, Ethics, and Membership and Professional Standards Committees as well as the OPTN Ad Hoc Geography Committee.

In 2017, Connecticut-based LifeChoice Donor Services affiliated with New England Organ Bank in Massachusetts to form New England Donor Services (NEDS). Its goal? To increase the number of organs available for transplant and create region-wide financial efficiencies.

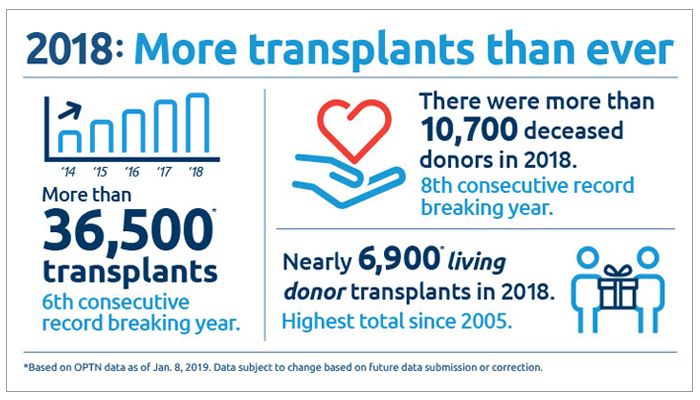

Two years into the affiliation, the number of donors and transplants has nearly doubled in the LifeChoice DSA—from 2016 to 2018, the Connecticut OPO experienced a 95 percent increase in donors and a 93 percent increase in transplants from donors.

Strategies for successfully increasing organ donation

NEDS CEO Alexandra Glazier explains the strategies to improve performance in the LifeChoice DSA were based on scaling successful interventions already in practice at New England Organ Bank.

“For NEDS, it was about implementing a combination of things we had proved were successful for NEOB. LifeChoice was in a similar culture and demographic in terms of service area, so we had confidence that the similar strategies would be successful.”

These include aggressively pursuing potential donors the community understands to be more complex—DCD donors, older donors and HCV+ donors. And adopting a vigorous utilization strategy for hard-to-place organs was also important.

But Glazier shares that the top strategy was to use highly specialized family service coordinators whose sole responsibility is to approach families for permission: “It’s not just that they are trained and skilled—but they have a significant amount of experience. Instead of approaching a small number of families each year, some of them are having over 80 donation discussions a year.” Maintaining this specialized staff with this level of experience requires a bandwidth of resources over a large service area.

Glazier says there are three strategies that have to be functioning at the same time to drive significant improvement for availability of organs for transplant. The first is getting more people to say yes to donation, whether through the registry or via family or surrogate authorization.

But she says that alone isn’t enough to solve the issue, so the second category is expanding the pool of what are considered suitable organs for transplantation—as is happening with HCV+ and DCD donors now.

Glazier adds it’s not just about recovering those organs: “The programs have to be transplanting them. So both sides of the system—donation and transplant—have to be operating in a coordinated way. It’s difficult to change a medical standard, you can’t legislate that—it’s medical practice, which takes some time to change.”

The third strategy necessary to drive change is leaning into technologies and innovations that help transplant five or six organs from a donor rather than two or three—in the future that could perhaps involve repairing organs in order to be able to transplant them.

Glazier sees these three strategies as necessary to propel improvement for the transplant system overall. “As OPOs we have a role in all three of these strategies. So when I consider how our organization is going to continue to drive improvement, I’m looking for micro-operational strategies that fall in all three of those categories.”

In 2017, Connecticut-based LifeChoice Donor Services affiliated with New England Organ Bank in Massachusetts to form New England Donor Services (NEDS). Its goal? To increase the number of organs available for transplant and create region-wide financial efficiencies.

Two years into the affiliation, the number of donors and transplants has nearly doubled in the LifeChoice DSA—from 2016 to 2018, the Connecticut OPO experienced a 95 percent increase in donors and a 93 percent increase in transplants from donors.

Strategies for successfully increasing organ donation

NEDS CEO Alexandra Glazier explains the strategies to improve performance in the LifeChoice DSA were based on scaling successful interventions already in practice at New England Organ Bank.

“For NEDS, it was about implementing a combination of things we had proved were successful for NEOB. LifeChoice was in a similar culture and demographic in terms of service area, so we had confidence that the similar strategies would be successful.”

These include aggressively pursuing potential donors the community understands to be more complex—DCD donors, older donors and HCV+ donors. And adopting a vigorous utilization strategy for hard-to-place organs was also important.

But Glazier shares that the top strategy was to use highly specialized family service coordinators whose sole responsibility is to approach families for permission: “It’s not just that they are trained and skilled—but they have a significant amount of experience. Instead of approaching a small number of families each year, some of them are having over 80 donation discussions a year.” Maintaining this specialized staff with this level of experience requires a bandwidth of resources over a large service area.

Glazier says there are three strategies that have to be functioning at the same time to drive significant improvement for availability of organs for transplant. The first is getting more people to say yes to donation, whether through the registry or via family or surrogate authorization.

But she says that alone isn’t enough to solve the issue, so the second category is expanding the pool of what are considered suitable organs for transplantation—as is happening with HCV+ and DCD donors now.

Glazier adds it’s not just about recovering those organs: “The programs have to be transplanting them. So both sides of the system—donation and transplant—have to be operating in a coordinated way. It’s difficult to change a medical standard, you can’t legislate that—it’s medical practice, which takes some time to change.”

The third strategy necessary to drive change is leaning into technologies and innovations that help transplant five or six organs from a donor rather than two or three—in the future that could perhaps involve repairing organs in order to be able to transplant them.

Glazier sees these three strategies as necessary to propel improvement for the transplant system overall. “As OPOs we have a role in all three of these strategies. So when I consider how our organization is going to continue to drive improvement, I’m looking for micro-operational strategies that fall in all three of those categories.”