Improvement

LifeLink of Georgia increases African-American organ donation

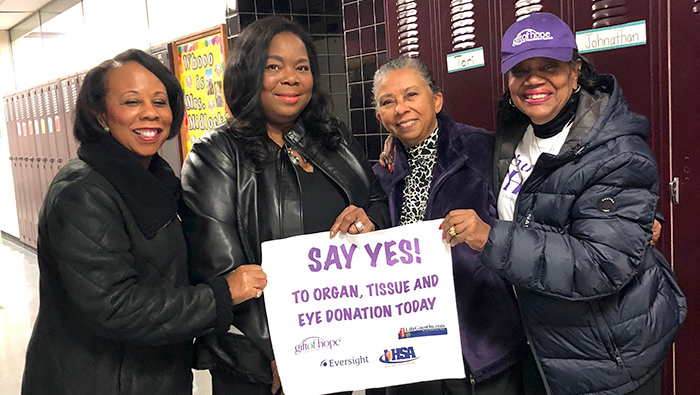

Bobby Howard, Director of Multicultural Donation Education at LifeLink talks about building trust in the community

Bobby Howard, Director, Multicultural Donation Education Program, LifeLink of Georgia

As a former NFL football player, Bobby Howard knows a lot about teamwork. A running back for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Green Bay Packers before an injury preempted his football career, he’s still active with his NFL community. So it makes sense that he brought a team approach with him to LifeLink of Georgia 24 years ago, when he was hired to develop and lead the OPO’s Multicultural Donation Education Program (MDEP).

Howard is a transplant recipient himself—he received a lifesaving kidney in October 1994 and joined the team at LifeLink the following year. Today, he leads a team of five MDEP staff with diverse community education experiences. Working across the state, they share a long range vision toward educating African-American and Hispanic communities about the need for organ donation. Through workplace and community partnerships, and by expanding staff and community involvement, LifeLink has been able to substantially increase donor registrations and family authorizations so that more transplants happen in Georgia.

LifeLink of Georgia serves more than 10 million people and includes nearly every county in the state, as well as a small pocket of South Carolina in the greater Augusta area. The African-American population in the region is 31 percent, almost triple the national average.

The impact of cultural awareness

When Howard came to LifeLink, it was to bring change. There was a considerable disparity between the number of African-Americans waiting for an organ transplant and the number of African-Americans registered to be organ donors.

One of the most impactful things LifeLink did was to become part of an organization called Concerned Black Clergy of Metropolitan Atlanta, an interfaith advocacy organization representing more than 150 churches.

“When we were recognized as a member it opened up a lot of doors,” explains Howard. “Especially in terms of reaching African Americans in the South, churches are very important. In the early days, some African Americans were hesitant to donate because of misconceptions about religious conflicts. So to tackle that you need to partner with the leaders.”

After early initiatives that targeted African-American health care professionals and involved aligning African-American donation specialists with African-American families, Howard and his team decided their highest value work was in reaching and educating people before a family needed to make the decision to donate and addressing concerns specific to the African-American community.

Says Howard, “A lot of people talk about cultural sensitivity, I don’t believe in that—I believe in cultural awareness. When you’re culturally aware and you can set aside biases, then you will be successful at talking to families and it doesn’t matter who talks to families. But we need to do that staff education first.”

The power of a plan

Howard acknowledges that what may be effective in reaching an African-American population may not be as successful in a Hispanic community, and vice versa: “I have a team member who works in the Hispanic community, and what he does in his community runs counter some of the things we do in the African-American community. He’ll do a health fair in a church and get 500 or more people to show up, and we’ll do a health fair in an African-American church and get 15 people. And even what works for me here in metro Atlanta may not work in south Georgia.”

Despite the differences among communities, what is true across the board is that donor families have the biggest impact. Howard’s team actively recruits black transplant recipients and donor families as volunteers. “Families who have not made that decision yet want to know why another family said yes,” says Howard.

LifeLink of Georgia has consistently been a top performer in registering African-American donors and gaining consent of families. Between 2007 and 2016, they experienced a total of 946 African-American deceased donors, surpassing all other OPOs. And in 2018, 118 African-Americans and their families consented to organ donation in the DSA , the most in any single year since the OPTN began collecting LifeLink’s data in 1988.

Howard’s recommendation to other OPOs? “You have to put a plan in place. It’s a lot of work to get there, and one of those things is trust from the community.”

Bobby Howard has served on the OPTN Board of Directors in addition to the OPTN Patient Affairs Committee. He currently serves on the Board of Directors of Donate Life America and is a past president of the Association of Minority Affairs in Transplantation (AMAT). He is president of the Atlanta chapter of the NFLPA Former Players Association.