Insights: FEATURE

When minutes matter

A look at the intersecting challenges in organ transportation, and a call for government and industry leaders to join the donation and transplant community in finding national-level solutions that ensure donor organs get safely to patients in need.

It is a story of perseverance against daunting odds, but it also illustrates the kinds of challenges the nation’s organ procurement organizations (OPOs) and transplant hospitals routinely face in making possible the more than 42,000 annual transplants in the U.S. Of course, not every day brings a blizzard, but every day transplant professionals do have to navigate the vital movement of lifesaving organs—as well as tissue samples for typing—through a labyrinth of ground and air carriers, weather events, unpredictable scheduling and more. And as the number of annual transplants has continued to grow, with some organs traveling greater distances to reach the sickest patients, the complexities have grown as well.

While Congress, media, and the public have shown a growing concern about organ transportation, OPO leaders and organ transportation experts point out that there is no one overriding problem, nor is there a universal nor easy fix that could ensure safe and efficient transport. Instead, they describe a variety of intersecting issues largely outside the control or oversight of the nation’s Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network (OPTN).

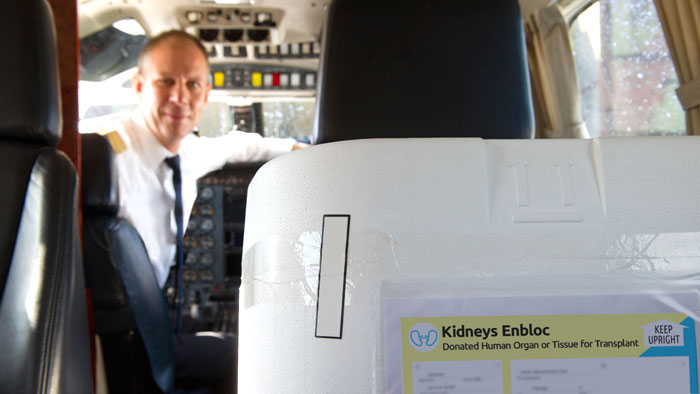

Organs are shipped as cargo

Before the terrorist attacks of 9/11, organs for transplant traveling by commercial air could be delivered directly to the cabin, where they often flew in the cockpit or under the immediate oversight of the flight crew. Changes put in place after 9/11, however, relegated unaccompanied donor organs to the cargo hold. Anyone who has ever had their luggage go missing or fail to make a connecting flight can recognize the perils of treating a human organ as, essentially, baggage. While a lost suitcase that takes a week to get to you is a hassle, a misplaced organ, with only hours of viability for transplant, puts someone’s life on the line.

“We have had our share of episodes where they didn’t put it on the plane or chose not to put it on—they didn’t put it on the last flight of the night because they figured it could just go in the morning,” says Ginny McBride, executive director of OPO OurLegacy Florida.

The problem is more, however, than just the increased risk of error when the donor organ becomes simply another piece of freight.

“Transplant is 24 hours a day, but cargo offices may not be.”

Casey Humphries, UNOS Solutions logistics service line leader

“Commercial air cargo is fraught with peril,” says P.J. Geraghty, vice president of clinical services for Donor Network of Arizona who also serves as vice chair of the OPTN OPO Committee. The same plague of cancellations, delays, and missed connections that make commercial flight a headache for travelers equally impacts the transport of organs, he points out. “If you have a connecting flight, it is really hit or miss.”

Kidneys, which are the most-transplanted organ, are the primary organ that travels by commercial air, meaning that the least reliable method of organ transport is the one OPOs have to rely on most often. “The largest volume problem we have in organ transportation is commercial air travel,” says Geraghty. “It is mostly kidneys, and commercial air is just not reliable.”

Further compounding the complexity of scheduling organs for commercial air transport is the fact that airlines require cargo to be delivered to the freight office as much as two hours ahead of the scheduled flight time—and even within the same airline, both “lockout time” policies and operating hours of the freight office can vary from airport to airport, says Geraghty. If a flight arrives at 6 a.m. but the cargo office doesn’t open until 8 a.m., nobody can pick up the delivery until it does.

“Transplant is 24 hours a day, but cargo offices may not be,” says Casey Humphries, logistics service line leader for UNOS Solutions, which develops tools, products and custom analytics for transplant hospitals, OPOs, researchers and other organizations involved with transplant. “There’s a patient on the other side who needs that transplant, and they need that transplant now, but no one can get the organ because it’s in the cargo office.”

Conversely, a donor organ recovered at 6 p.m. might be too late to make the lockout-time window before the cargo office closes for the night. As a result, “Transportation starts to drive when you want to go to [recovery] surgery,” says McBride. “And for OPOs without donor care units, that is hard. You can’t tell the hospital when you are going to the OR—they tell you.”

One workaround for cargo lockouts is sometimes to send the organ accompanied by a courier with TSA clearance to bring it onboard as carry-on luggage. However, with many flights overbooked, it can often be impossible to get a last-minute ticket.

There’s a shortage of available charter aircraft

Charter flights are often essential transportation for transplant teams recovering hearts, lungs and most livers, which must be transplanted within a few hours of recovery. On occasion, OPOs must resort to charter flights to transport kidneys when no other options are available. A convergence of factors have both driven up the cost and limited the availability of charter aircraft.

There is a nationwide shortage of pilots, both charter and commercial, that is only expected to grow worse as a generation of older pilots retires without enough younger pilots to replace them. In addition, the pandemic has driven a shift to private and charter planes by businesses and wealthier travelers, exacerbating the pilot shortage and creating more competition for available charter flights.

Even if planes can be found, increased demand, along with higher fuel and other costs, has driven up the price of charter flights.

“There are transplant centers losing out on transplants because they don’t have access to charters,” says Geraghty.

Even if planes can be found, increased demand, along with higher fuel and other costs, has driven up the price of charter flights. A short flight might be $10,000. Longer charters can easily run well above $20,000.

“The cost of chartering because of fuel and equipment has skyrocketed in the last 10 years, and the availability of planes and more specifically of pilots for those planes has become more of an issue,” says Jeff Orlowski, president and CEO of OPO LifeShare of Oklahoma. “It’s not unusual for an OPO to have to have a plane flown in from several hundred miles away and ultimately that all gets added into the cost of the transplant. We just chartered two kidneys and it was a $25,000 add-on. That is a very expensive undertaking to do on a routine basis—assuming you can even find a plane.”

Courier companies are short-staffed

“What happens to society happens to the transplantation system,” points out McBride of Our Legacy Florida. “When COVID happened and the airlines shut down, that made it so much harder for us. When the economy goes bad, our system is affected too.”

Similarly, staffing shortages plaguing many service industries are affecting courier companies as well: “Because people have left the workforce, courier companies don’t have the personnel they need to respond to a timely request,” says McBride. “Coordinators sit on hold with a courier company for an hour just to get someone to answer the phone so we can set up a job.”

LifeShare of Oklahoma faces similar difficulties, says Orlowski. “It is not unusual for us to send blood to two or three different cities and three or four different transplant centers for typing, and finding couriers and flights to reliably get blood and tissue samples moved around for cross-matching in a timely fashion is frequently problematic. They are in short supply and not necessarily reliable.”

More organs are traveling, and they are traveling greater distances

In 2022, the U.S. surpassed a milestone 1 million transplants since the first successful transplant took place in 1954—and it also marked an individual record-setting year of more than 42,800 transplants, which included more than 25,000 kidney transplants. This growth continues a trend that has seen the number of annual transplants in the U.S. more than double over the past 20 years.

Continuing improvements in the nation’s donation and transplant system that have contributed to this growth include new organ allocation polices that are helping to increase equity and balance wait times around the country. By prioritizing the sickest patients, no matter where they live, the policies may result in organs traveling further.

More organs—particularly kidneys—and tissue-matching samples moving more often and over greater distances “increases the strain on an already difficult-to-navigate transportation ecosystem,” points out UNOS’ Humphries.

Orlowski notes, for example, that the majority of the kidneys overseen by LifeShare of Oklahoma used to be transplanted within 125 miles of the OPO’s offices: “Now, we have long-range shipment to multiple different centers in multiple different cities. We have typing materials going to California and the East Coast for the same donor.”

Transportation providers are not accountable to the system that depends on them

Undeniably, there are outstanding and dedicated people at every stage of the transport process, from couriers to cargo handlers to charter companies, who do everything they can to make sure these shipments get where they need to go safely and efficiently. Yet the fact remains that while transportation plays an essential role within the donation and transplant system, when errors or failures occur, the transportation carriers are not accountable to or subject to any oversight by the OPTN.

“At some point, whether it’s an airline or charter company or courier, the OPO and the transplant center have to rely on a contractor of some type to move an organ,” says Orlowski. “There is a component that UNOS, the OPTN, OPOs and transplant centers—none of the players being held accountable or being criticized—actually controls.”

McBride agrees, “You are reliant on a system of people with no connection to the OPTN, but upon whom we are beholden to do that work.”

“Our focus has been too often ‘Let’s just get the job done and move on to the next case,’ …

… and we don’t take the time to quantify this and make it more transparent. Transportation and allocation are inextricably linked, and I am encouraged that people are starting to see that.”

Ginny McBride, Executive Director, OurLegacy

The problems have been largely invisible

Even as the complexities of transporting organs and tissue samples have increased, OPOs have remained focused on getting the job done, with each OPO patching together its own strategies, workarounds, and network of carriers. Despite the challenges, it’s very rare for an organ to be lost, damaged, or to arrive too late to be transplanted.

“We [LifeShare of Oklahoma] haven’t lost an organ, we haven’t had one not be transplanted because it missed a flight. We haven’t not been able to get an organ transported if we need to,” says Orlowski. “It’s not easy, it’s expensive, but we get it done.”

However, there’s growing recognition not only that such a case-by-case, OPO-by-OPO approach isn’t sustainable as the number of transplants continues to increase, but also that transportation issues need to be more broadly recognized, understood and addressed at a system-wide level, particularly as new allocation policies are developed.

“Our focus has been too often, ‘Let’s just get the job done and move on to the next case,’ and we don’t take the time to quantify this and make it more transparent,” says McBride. “Transportation and allocation are inextricably linked, and I am encouraged that people are starting to see that.”

Arizona’s Geraghty notes, for example, that his OPO’s territory and Los Angeles are only an hour apart by commercial air. “So why does it take eight hours to get from point A to point B?” he says. “There has been no good systemic data about what happens to organs between cross-clamp time and reimplantation time.”

“Everyone in the donation and transplant community wants to make sure that every donor organ gets safely to a patient in need. But our community alone can’t solve these transportation challenges.”

Matthew Cooper, M.D., immediate past president of the OPTN board of directors

Seeking solutions together

In January 2023, UNOS CEO Maureen McBride outlined an agenda calling for actions to strengthen the U.S. donation and transplant system, including steps to improve safety and accountability in organ transport.

In July of 2023, the U.S. House of Representatives approved its 2023 Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) reauthorization bill, which included a provision to require the Secretary of the Department of Transportation (DOT), in consultation with the FAA Administrator, to convene a working group to develop best practices for the transportation of an organ in the cabin of an aircraft rather than in the cargo hold. This change could eliminate cargo lockout times and ensure a more direct chain of control for donor organs.

The provision included in the House version of the FAA reauthorization bill is the result of ongoing advocacy by UNOS, OPOs and other members of the nation’s organ donation and transplantation community. UNOS has engaged with the FAA leadership, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), the Department of Transportation (DOT), and members of both the House and Senate to pursue this reform.

In addition, UNOS is advocating for a system-wide requirement that GPS trackers be used in the transport of all unaccompanied donor organs, regardless of anticipated travel distance. UNOS’ own Organ Tracking Service (OTS), first made available nationally in 2021, is currently in use by nearly a third of the nation’s OPOs, including Donor Network of Arizona, which tracks almost every organ, accompanied or not, with an OTS device.

The cost for tracker and service combined is about $1,000 per year, but for OPOs using OTS with high frequency, “the cost works out to about $5 to $10 per shipment,” says UNOS’ Humphries, who oversees the service.

The real value the trackers offer is peace of mind. If the organ doesn’t take off with its scheduled flight, if it’s misplaced in a cargo office, if a courier is stuck in rush-hour traffic, the OPO can see where it is and respond as needed. Before OTS, “We had organs get delayed or even lost in transit to their centers,” says Geraghty. “I’ll gladly pay for tracking not to have to go through that again.”

Humphries cites a case where an organ, sent with a courier, had only one hour to make a flight—and the tracker showed it heading in the wrong direction from the airport. It turned out the courier had been dispatched for another pickup, but alerted to the problem, the OPO was able to intervene and the organ made the flight. “When minutes matter,” says Humphries, “the tracker saves a lot of time.”

![]()

UNOS began piloting its Organ Tracking Service (OTS) in 2020 and launched a fully featured service in 2021 that is available to all OPOs nationally. 4G tracking updates every two minutes and auto calculates and updates flight ETAs. A user portal also offers detailed visualizations and full integration with DonorNet and TransNet.

Data is needed

As more organs are tracked, the data generated will help build a more comprehensive picture of the movement of organs. Centralizing and publicly reporting this data, as well as investigating any cases of organs impacted by logistics, are also actions UNOS has called for.

“As we have made changes in organ allocation policy, the big blank spot in all of that has been transport,” says Geraghty. “No one had good data on what impact allocation policy would have on transport and vice versa, and now the community will have better data.”

“It’s not just about what one OPO can learn, it should be what every OPO can learn by putting our data together,” adds Ginny McBride. “A comprehensive set of data would help us understand the successes, the near-misses, and the failures of transportation.” Also on her and other OPO’s wish lists is “a commercial transportation system that was geared to our needs,” she says.

Orlowski envisions “some kind of a national cooperative network of charter companies that are all bought into this and provide priority services, so that instead of us individually contacting charter companies we could call some central dispatch that could get a plane for us starting as close by as possible.” Another solution he suggests could be a centralized service coordinating the nationwide movements of organs, transplant teams and tissue samples to enable greater efficiency throughout the system.

Such national-level solutions will be essential to ensure safety as the number of annual transplants continues to grow, says Matthew Cooper, M.D., immediate past president of the OPTN board of directors. “Everyone in the donation and transplant community wants to make sure that every donor organ gets safely to a patient in need. But our community alone can’t solve these transportation challenges. We urgently need government agencies and transportation industry leaders to join us at the table to develop an integrated, nationwide solution to make organ transportation safe, efficient and reliable.”