Improvement

Stronger together

A collaborative study between U.S. and U.K. researchers reveals shared learning opportunities that could spur increased kidney utilization rates.

Opportunities to increase kidney utilization

Contrasting the kidney discard rates in the United States with those in the United Kingdom—approximately 18 to 20 percent and 10 to 12 percent, respectively—suggests a significant difference in how the two countries utilize the organ. At first glance, the U.K. appears more successful at utilizing deceased donor kidneys than the U.S., but research published recently in the American Journal of Transplantation reveals the inadequacy of this kind of simple comparison.

“Fundamental system differences mean U.S. and U.K. utilization rates are not directly comparable,” said Maria Ibrahim, who is a clinical research fellow at the U.K.’s National Health Service Blood and Transplant. Ibrahim collaborated with United Network for Organ Sharing principal research scientist Darren Stewart, chief medical officer David Klassen, M.D., and research analyst Gabe Vece for more than a year on the AJT manuscript, which is featured on the May 2020 cover of the journal’s print issue.

The article reported on findings from a collaborative study among the U.S. and U.K. researchers that was aimed at developing a deceased donor kidney utilization metric, which would allow for meaningful comparisons of kidney utilization rates between the two countries. “We worked with colleagues connected to what amounts to UNOS of the U.K. for more than a year analyzing data,” Stewart said. The researchers’ findings challenge a conventional wisdom in the organ donation and transplantation community that kidney discard rates among countries are directly comparable.

“To our knowledge, this is the first reported international collaborative study attempting to identify directly comparable organ utilization metrics in deceased donor kidney transplantation,” Stewart said, adding that findings from the study could help researchers pinpoint where the greatest opportunities for improvement lie within the multistep process of transplanting a usable kidney from a deceased donor.

Analyzing transplantation accuracy

“To compare ‘like with like’ a detailed understanding of each national transplantation system is required,” explained Klassen. To that end, the researchers spent more than a year analyzing data from 102,526 deceased donor kidneys from the U.S. and 12,780 deceased donor kidneys from the U.K., which were recovered between 2006 and 2017.

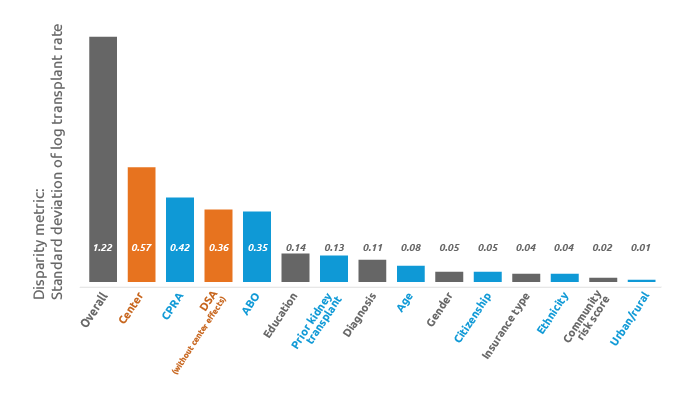

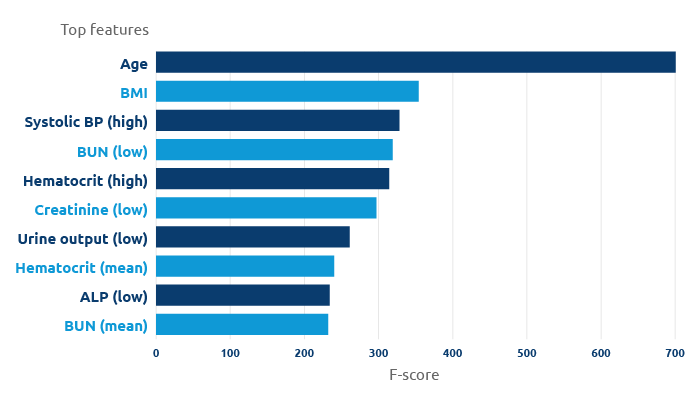

Factors such as donors’ age and kidney donor risk index, or KDRI, were assessed to determine if discard rates could be accurately compared between the two countries. Ultimately, the researchers determined that they could not. “Though a linguistically similar benchmark utilization rate was applied to both countries’ data, central differences in practice require direct intercountry comparisons be made cautiously,” Klassen said.

For example, while both countries traditionally define their organ discard rate as the percentage of kidneys recovered for transplant that are not transplanted, in the U.K., kidneys are almost never recovered prior to transplant program acceptance, whereas pre-acceptance recovery is relatively common in the U.S. “These measures are skewed by the common practice in the U.S. of recovering kidneys prior to obtaining transplant center acceptance, compared to the U.K.’s practice of recovering conditional on acceptance,” Ibrahim said. Hence, the U.K. discard rate reflects post-acceptance dynamics such as transportation and logistical issues, prospective recipient instability, and discovery of renal defects, “whereas U.S. discard rates reflect these possibilities, as well as kidneys that were recovered but not accepted by any U.S. transplant center,” added Ibrahim.

Bidirectional learning opportunities

Organ donor age also plays a role in kidney utilization rates. At 10.7 percent of all deceased donor kidneys transplanted, the proportion of transplanted kidneys from elderly donors in the U.K.—people ages 70 and older—was 18 times greater than in the U.S., in which 0.6 percent of all deceased donor kidneys came from elderly donors. Additionally, the median age of both recovered and transplanted kidney donors tended to be substantially older in the U.K. compared to the U.S.

“This study has demonstrated marked differences in kidney donor populations between the U.K. and U.S., which are increasing over time, highlighting the need for shared learning,” Vece said, adding that U.S. transplant professionals may benefit from U.K. colleagues’ experience in the use of kidneys from older donors and those with higher KDRI. “It has previously been shown that similar ‘higher risk’ kidneys have excellent one-year post-transplant graft survival in the U.K., suggesting that expanding U.S. kidney utilization in these ways is feasible, even in the current regulatory environment,” said Chris Callaghan, who is the national clinical lead for abdominal organ utilization at NHS Blood and Transplant and co-author on the published research.

By contrast, the researchers found higher utilization in the U.S. of both “en bloc” kidneys (from very small donors) and kidneys from donors with higher creatinine levels (possibly acute kidney injury cases), suggesting bidirectional opportunities for shared expertise in kidney utilization.

A global issue

Nearly 40,000 organ transplants were performed in the U.S. in 2019, making last year the seventh consecutive record-breaking year for organ transplantation. Of that total, 23,401 were kidney transplantations. But despite the increasing trend, the need for organs in the U.S. far exceeds the supply. More than 94,000 kidney transplant candidates remain on the country’s waiting list today. “Organ shortage in transplantation is a global issue,” Stewart said. “It is essential that organs procured from deceased donors are utilized as efficiently and effectively as possible.”

Stewart and his colleagues were motivated to uncover the sources of disparities in deceased donor kidney discard rates between the U.S. and U.K. so that organ and transplantation professionals in the two countries could learn from one another. Due to transplant system differences between the two countries, a single utilization rate metric that would allow a fair adjudication of which country had “better” kidney utilization was not identified but, the researchers were galvanized by the opportunities for collaboration and shared learning that the research process uncovered.

“To spur global learning, future international registry collaborations should pursue even richer cross-country comparisons of utilization rates,” Klassen said.

Looking ahead

Though at face value, dividing the number of kidneys transplanted over the number of kidneys retrieved for the purposes of transplantation does not produce a comparable number, Klassen suggested that perhaps expanding the denominator to include potential donors and comparing utilization trends over a longer period of time could serve as a potential solution for comparison.

“There are many global learning opportunities to be had from shared registry studies,” Ibrahim said, adding that she plans to explore the area of research further in future collaborations with UNOS researchers. “Methods employed in this study could be translated to other international transplant registries in pursuit of further global learning opportunities.”

Research findings published in the May 2020 issue of American Journal of Transplantation (Vol 20, Issue 5)