Insights: FEATURE

Will organ perfusion transform transplantation?

A look at the rapidly evolving organ perfusion technology that could make more organs available than ever before.

Across five decades of advances in transplant medicine, static cold storage (SCS) has remained a largely unchanged but vital link in the chain between donor and recipient. Yet SCS has well-recognized limitations. SCS slows, but doesn’t prevent, ischemic injury, which in turn increases the risk of graft non-function, ischemia reperfusion injury, primary graft dysfunction, and other post-transplant complications in the recipient. In addition, only a limited assessment of the organ is possible during SCS, making it difficult to accurately predict how well an organ may function following transplant.

Now, however, the rapidly advancing technology of ex vivo normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) holds promise for improved preservation, better assessment and even reconditioning of organs before transplant. And while many questions remain to be resolved regarding the implementation of this still-young technology, already NMP has had an important impact on transplant medicine in the U.S. (and globally), expanding the donor pool by allowing surgeons to assess and successfully transplant organs that once would have gone unutilized.

In comparing NMP with SCS, a primary benefit NMP appears to offer is the luxury of time …

Preserving time for transported organs

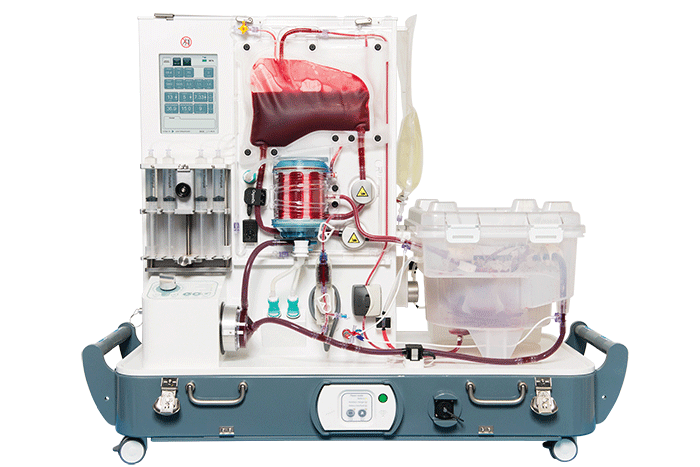

The basic principle of NMP technologies is to approximate “near physiologic” conditions of temperature, nutrients and oxygen outside the body and to enable the organ to function much as it would within the body. Videos of ex vivo NMP vividly illustrate the concept—a heart beats, lungs expand.

In comparing NMP with SCS, a primary benefit NMP appears to offer is the luxury of time. Although a safe time limit has not yet been established for NMP, clinical evidence suggests that organs are substantially protected from ischemic injury while being perfused. In essence, NMP “stops the clock” on ischemic injury. “Extending preservation time is a clear benefit, and that is solid and well-established,” says UNOS chief medical officer David Klassen, M.D., who is former director of the kidney and pancreas transplant programs at University of Maryland Medical Center.

NMP may make it possible, then, for organs to be transported over greater distances, for recipients to travel further to a transplant hospital, and for surgeons to have more flexibility to schedule optimal surgical times and increase surgical time for complex recipient cases.

In essence, normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) “stops the clock” on ischemic injury.

Developing organ perfusion technology

Three companies are currently leading the development of ex vivo NMP in the U.S., with devices in current and/or recently completed clinical trials.

Massachusetts-based TransMedics offers the transportable Organ Care System (OCS) devices for heart, lung, and liver; OrganOx, based in the UK, has developed the metra® transportable perfusion device for liver; and Swedish-headquartered XVIVO Perfusion offers the non-transportable XPS lung perfusion system.

A fourth company, Lung Bioengineering, based in Maryland, has focused on making perfusion technology more widely accessible by developing a centralized, free-standing perfusion facility to serve multiple organ transplant hospitals. The facility employs both the XPS and the Toronto EVLP System developed at University Health Network in Toronto, Canada.

Assessing function and expanding the organ donor pool

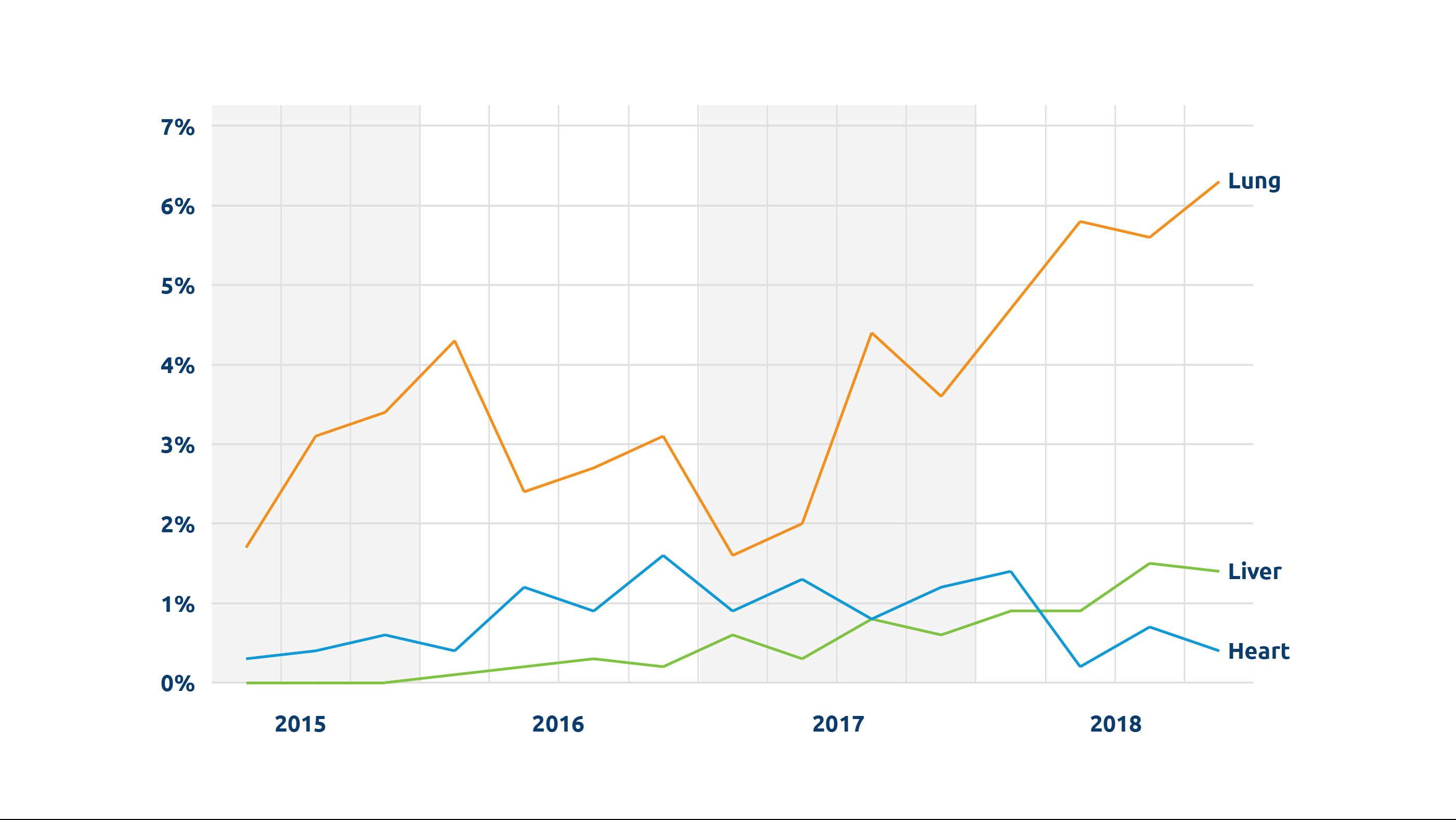

Perhaps most important among its many potential benefits, NMP makes it possible for organs to be functionally evaluated. When surgeons have had to make educated judgements about the condition of donor organs, potentially usable organs—particularly those considered “marginal” or “extended criteria”—have inevitably gone unutilized. This problem is a particularly critical factor in the low utilization rate for donor lungs; only about 20-25 percent of lungs are transplanted from all deceased donors, according to UNOS research scientist Rebecca Lehman, PhD, and more than half are never even recovered for the purpose of transplant.

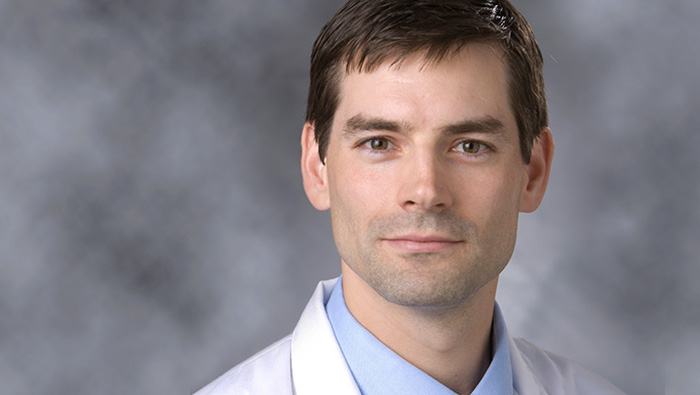

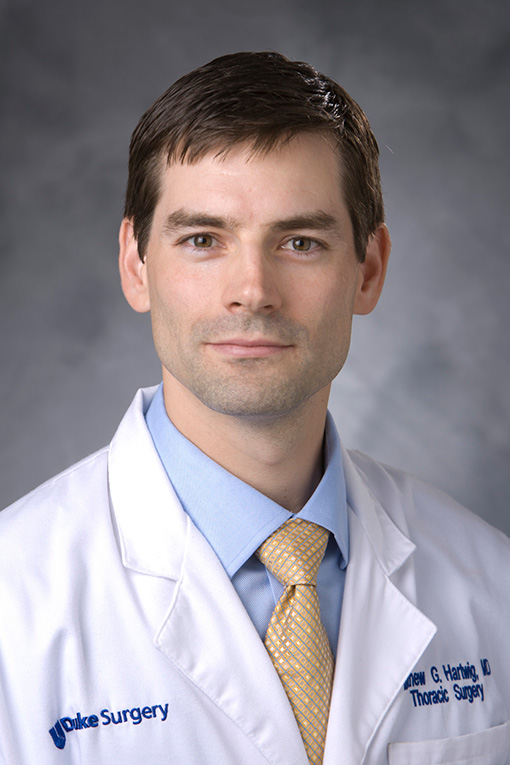

But with NMP, says Duke University lung transplant surgeon Matthew Hartwig, M.D., “The devices allow us in a very safe and reproducible fashion to assess the lung outside of the complex environment of the donor and to evaluate the function of the lung in isolation.” Using NMP through clinical trials at Duke has made it possible to more objectively determine which organs are most likely to be successfully transplanted, says Hartwig. As a result, “We have been able to utilize some lungs that otherwise would not have been used for transplant, but that could have been and should have been,” he says.

One such trial was Lung Bioengineering’s multicenter Phase 2 clinical trial, which ended in August 2018. Initially unacceptable lungs were transported to the company’s Silver Spring, Maryland perfusion center to be assessed. All lungs that were deemed acceptable after being evaluated via NMP were successfully transplanted.

“If they do well in ex vivo, they do well in transplant,” confirms transplant surgeon Pablo Sanchez, M.D., Ph.D., director of the ex vivo lung perfusion program at the University of Pittsburgh, another of the Lung Bioengineering clinical trial locations.

OrganOx metra®, a transportable liver NMP device now in clinical trials in the U.S.

Comparable benefits have been seen for other organs. In a UK trial of the OrganOx metra®, a transportable liver NMP device now in clinical trials in the U.S., 31 livers initially declined by all seven UK liver transplant hospitals were assessed on the device, and 22 were successfully transplanted, according to OrganOx CEO Craig Marshall.

As Marshall notes, there is risk associated with lack of information about an organ. Being able to assess an organ ex vivo and make an informed decision increases information and decreases that risk. Clinical data thus far seem to indicate comparable outcomes for initially unacceptable or extended-criteria organs transplanted following assessment via NMP—offering the promise that many more organs, such as those from DCD donors, will prove safe for transplant to help address critical shortages.

Video courtesy of XVIVO Perfusion

Lung Bioengineering’s EVLP Suite

Up close

Leading the Way

Meet the companies developing ex vivo NMP in the U.S.

OrganOx, Oxford, England, metra® transportable perfusion device for liver

XVIVO Perfusion, Gothenburg, Sweden, Non-transportable XPS lung perfusion system

Lung Bioengineering, Silver Spring, Maryland, Centralized, free-standing perfusion facility serving multiple transplant centers

Future potential, future questions

Beyond the immediate benefits already being demonstrated, NMP technology is widely believed to have the potential to powerfully transform the future of organ transplant medicine.

Although clinical trials have focused on demonstrating the safety of using ex vivo NMP before transplant, researchers and transplant professionals believe the same technology will likely soon make it possible to improve the condition of recovered organs or even treat them therapeutically for problems such as bacterial or fungal infections, with the goals of further expanding the donor pool and also improving post-transplant outcomes for recipients.

In the long term, biotechnology experts hope organs could be modified through ex vivo perfusion to prevent or reduce the need for anti-rejection medications, a development that could support advances in xenotransplantation—the modification of nonhuman organs to use in human transplant.

For now, however, basic questions still need to be addressed in the implementation of this technology:

- What criteria should determine whether an organ is perfused, or should NMP become standard protocol for all donor organs?

- Where, when, and for how long should NMP be applied?

- Will the possible benefits of NMP outweigh the costs (including equipment, training, and personnel) of implementing this technology, and how will those costs be distributed across the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network?

“We still have a lot of work to do as a community to determine what is going to be the best way to perfuse, evaluate, rehabilitate and eventually improve the organ in an ex vivo setting,” says transplant surgeon Matthew Hartwig. Nevertheless, he believes the day will come when “the idea of cold storage will be a historical footmark that people will chuckle about as the way we used to do transplant.”

Note: Originally published on April 8, 2019