Improvement

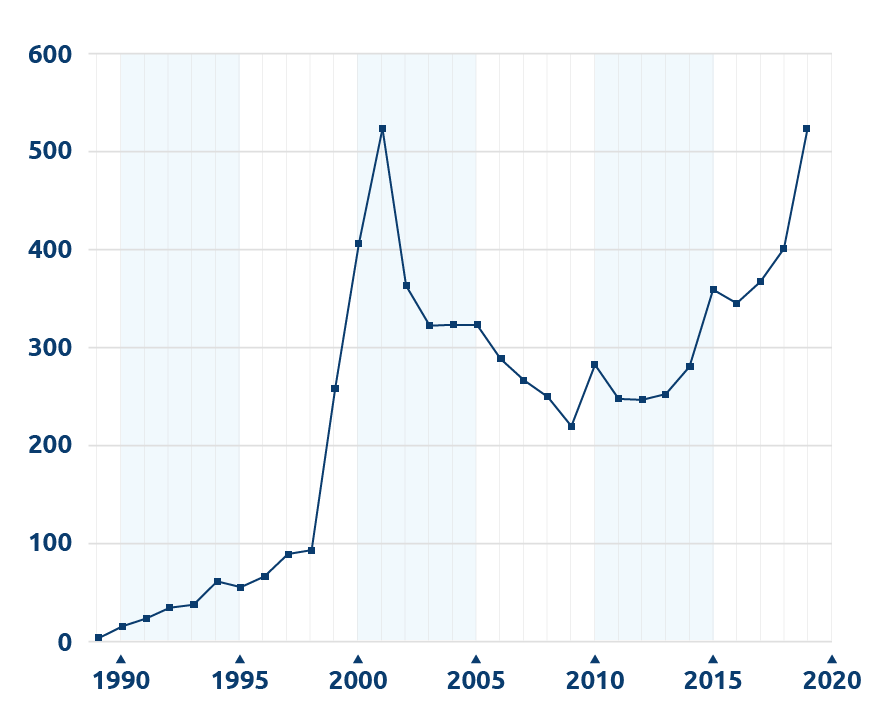

Then and now: Living donor liver transplantation

Transplant programs continue to refine and transform the procedure.

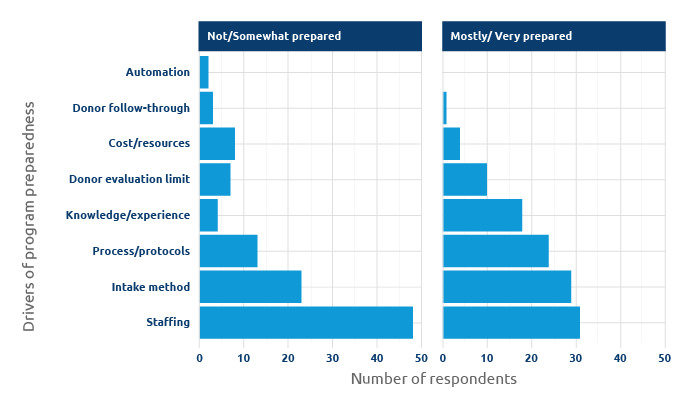

Living liver donor transplant volume in the US, 1989 – 2019

Based on OPTN data as of Mar. 23, 2020. Data subject to change.

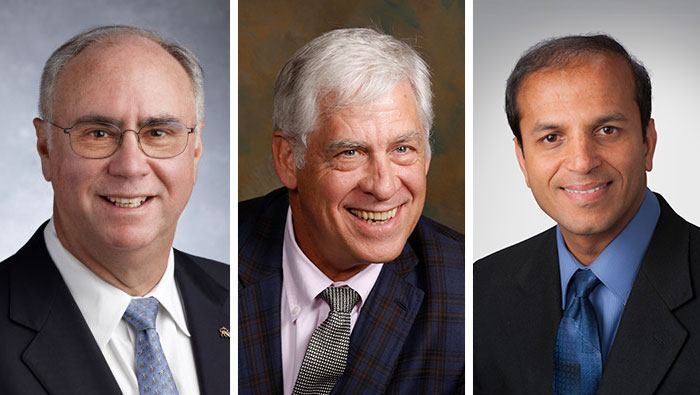

Living donor liver transplants have been performed in the U.S. for about 20 years. Over that time the number of procedures has grown sharply, fallen back and is now rebounding (see chart). United Network for Organ Sharing recently talked with three liver transplant surgeons for insights into the history of the procedure in the U.S. and its current role in treating liver failure.

Early history of living donor liver transplants

Living donor liver transplantation grew out of the use of segmental or split liver transplants from deceased donors. As those procedures showed success in the 1980s, transplant teams began considering living donation to provide a liver segment for a recipient.

Clinicians around the world simultaneously investigated the procedure. “Much of the early development started in Asia,” noted Charles Miller, M.D., director of liver transplantation at the Cleveland Clinic. Some Asian nations had not yet adopted brain death legislation, thus limiting the availability of deceased donors.

A transplant team in Brisbane, Australia, reported success with a living donor liver transplant in July 1989 from a mother to her infant son. Beginning in November 1989, clinicians at the University of Chicago Medical Center began performing a series of adult-to-child transplants.

1989

July 1989: successful living donor liver transplant in Brisbane, Australia

November 1989: University of Chicago Medical Center clinicians began performing adult-to-child transplants

Other transplant programs learned about and applied the procedure in different ways. Some University of Chicago faculty relocated and brought their experience to other hospitals. Some clinicians, such as Miller, traveled to Chicago to learn. Others, such as the University of Minnesota Medical Center, independently developed protocols. “We mostly just started on our own,” said Abhinav Humar, M.D., who began his career at the University of Minnesota Medical Center. Humar is now chief of transplantation at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Technical and ethical challenges

An early challenge was determining the amount of liver mass that can be safely recovered from a living donor while also supporting the recipient. For adult-to-child transplants this is somewhat less of a concern, as the smaller left lobe of the liver is often sufficient.

2001

More than 500 living donor liver transplants had been performed nationwide.

2002

Introduction of the model for end stage liver disease, or MELD

As the procedure expanded to adult-to-adult transplants, more programs began using the larger right lobe of the liver. “Once people started using more right lobes — in about 1997 to 1998 — the number of transplants really began to take off,” Miller said. By 2001, more than 500 living donor liver transplants had been performed nationwide.

In the next few years, volume dropped substantially. This may have been due in part to a few living donor deaths, which caused a number of programs to re-evaluate their protocols. While each incident was carefully studied, “each seemed unique,” said John Roberts, M.D., chief of the Division of Transplantation at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center. Thus it was difficult to see a pattern that might suggest a particular change in practice.

Humar acknowledged the inherent risk of living donation. “Every adverse event gives us an opportunity to learn and improve,” he said. “That said, if we have the default position that a procedure should be ‘zero risk,’ then that procedure probably will never happen. There is some risk. We accept that risk with the selfless act of donation, and we try to decrease it as much as possible.”

A greater reason for the decrease may have been the introduction of the model for end stage liver disease, or MELD, system in 2002. “When programs first started doing adult-to-adult transplants there were a lot more potential recipients in need,” Roberts said. “MELD did better at taking care of people who needed transplants urgently. It decreased the need for living donor transplants for some.”

Living donor transplants now balance patient and donor risk. Roberts noted some candidates in high-MELD areas are “not sick enough” to be transplanted soon with a deceased donor liver, but they are at increased risk of a catastrophic event if they continue to wait; thus they would benefit from a living donor transplant. Others have a disease such as metastatic colorectal cancer that may be treatable with a timely transplant, but for which the MELD system doesn’t provide priority for a deceased donor transplant. “If there is a potential living donor who understands and accepts the risks, that may be the only option,” Roberts said. “It may be a better potential outcome for the recipient than not getting a transplant.”

Changes in capabilities, knowledge, approach

Today

Combined learning from Asian transplant programs and new technology is helping to grow programs.

New technology has helped clinicians assess and plan the living donor liver transplant procedure. This is especially true with radiologic imaging software. “In the last few years it’s gotten more accurate and detailed,” Humar said, adding that his team is looking at pairing radiologic imaging software with 3D printing and modeling technology to provide clinicians with a better idea of donor anatomy and size.

Many clinicians continue to learn from the expertise of transplant programs in Asia. “At some centers, they may do 300 transplants a year,” Roberts said. “[Asian programs] have taught us a lot about technical issues. There is definitely a learning curve, probably not just the total number of procedures but doing more in a short amount of time.”

Humar said his program is “changing the mindset” of the role of living donor transplantation in treating liver failure, to regard it as a first option for many candidates. “In the deceased donor system, there are many potential transplant candidates for any one potential donor available,” he said. “With living donation, the equation is one-to-one.” As with any medical therapy, he says the challenge is to demonstrate it provides an advantage over any other care currently available.