Innovation

Building a new, more flexible system for organ allocation

How multi-criteria decision-making methodologies and big data analytics are helping to design continuous distribution policies

What is continuous distribution?

When will it be implemented?

Who are our partners?

How do we build continuous distribution policies? James Alcorn, UNOS senior policy strategist, says that when the OPTN Lung Transplantation Committee began formulating an answer to this question in 2018 they recognized continuous distribution was a nebulous concept: “It was so new and seemed so theoretical that it was hard to put into concrete terms what it would actually mean in practice.”

The objective was to create an evidence-based algorithm that makes every candidate attribute used by the match run comparable through a flexible points-based system, eliminate the hard boundaries that exist in the current classification-based system, and pave the way for the patients with the greatest medical need to be transplanted more quickly.

Clinical and value-based elements

To get there, the team needed to understand not just the clinical part of how to assign points for attributes like waitlist urgency, but also what the value-based judgments should be in a new policy—for example, how important should medical urgency be in prioritizing patients versus candidate biology or organ placement efficiency?

To help determine what a new policy should look like, the team first chose to establish a baseline for comparison by translating current lung policy into the continuous distribution, or points-based, framework. They had to find a way to quantify the influence each candidate attribute has in determining the preferential order of candidates (a match run) offered an organ when donated lungs become available.

Decision making methodologies

By applying a multi-criteria decision making methodology called revealed preference analysis to OPTN data from thousands of match runs, the team built a mathematical model—an approximation of the system—to help them understand the underlying preferences inherent in current OPTN lung allocation policy. The results of these analyses have been informing the design of the new framework and are helping to ensure that it will more equitably determine patient priority on the waiting list.

The team also employed a second multi-criteria decision making methodology, Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), to help the committee and community revisit these value judgements and develop the new continuous distribution policy.

“We needed to create a model that allows us to distinguish clinical decisions from ethical ones so that we can then decide as a community what value should be placed on each,” explains Alcorn.

Fast-forward to today, and hear from Alcorn, UNOS Principal Research Scientist Darren Stewart, and UNOS Research Scientist Rebecca Goff about how this mixed method approach to policy-making is helping to bring the concept of continuous distribution to life and transforming the future of organ allocation.

Q&A

Building continuous distribution:

How a concept took shape

At a glance

Transplanting patients more quickly

The framework moves organ allocation from placing and considering patients by categories such as blood type to considering multiple factors all at once using an overall score. This ensures that no single factor in the match run determines priority for donated organs. It was approved by the OPTN Board of Directors in 2018 as the model for future policy development. Beginning with lung, continuous distribution will establish a single, consistent and transparent allocation system for all organs. Learn more.

James Alcorn, UNOS senior policy strategist

Darren Stewart, UNOS principal research scientist

Rebecca Goff, UNOS research scientist

How do you measure value judgment in policy-making?

Stewart: When we talked about coming up with a formula for what should be used to rank order patients, we wanted it to be as evidence-driven as feasible. And where there’s a need for a value judgment, where clinical data isn’t going to tell you how much efficiency should be valued over utility, then that needs to be a conversation about what the community values. There are structured mathematical ways to find out. We were able to approximate current policy based on a large number of classifications and rank ordering within that classification into a fairly simplistic composite score that’s 80 – 90 percent correlated with the actual match run, to quantify value judgements embedded into the current policy, as a starting point in the conversation.

Stewart: When we talked about coming up with a formula for what should be used to rank order patients, we wanted it to be as evidence-driven as feasible. And where there’s a need for a value judgment, where clinical data isn’t going to tell you how much efficiency should be valued over utility, then that needs to be a conversation about what the community values. There are structured mathematical ways to find out. We were able to approximate current policy based on a large number of classifications and rank ordering within that classification into a fairly simplistic composite score that’s 80 – 90 percent correlated with the actual match run, to quantify value judgements embedded into the current policy, as a starting point in the conversation.

What is revealed preference analysis?

Alcorn: Revealed preference analysis looks at the underlying preferences that drive our decisions and is one of a wide variety of methods we’re using in complementary ways. It’s part of a field called operations research that deals with multi-criteria decision-making, or when you have a complex problem that has multiple goals. Organ allocation obviously has multiple goals, including equity, utility and efficiency, so how do we figure out how to balance those different goals?

Alcorn: Revealed preference analysis looks at the underlying preferences that drive our decisions and is one of a wide variety of methods we’re using in complementary ways. It’s part of a field called operations research that deals with multi-criteria decision-making, or when you have a complex problem that has multiple goals. Organ allocation obviously has multiple goals, including equity, utility and efficiency, so how do we figure out how to balance those different goals?

Stewart: It’s essentially what’s known as ‘discrete choice modeling,’ but using observational data—in this case from computer-generated match runs—as opposed to experimental data gathered from asking human beings their preferences.

Stewart: It’s essentially what’s known as ‘discrete choice modeling,’ but using observational data—in this case from computer-generated match runs—as opposed to experimental data gathered from asking human beings their preferences.

What were you trying to find by applying revealed preference analysis to organ allocation policy?

Alcorn: We looked at past decisions that had been made and are embedded into policy in order to figure out what that revealed about the preferences—value judgments—that could impact who might get an organ and who might not in the match run. We wanted to determine what the balance is in current policies.

Alcorn: We looked at past decisions that had been made and are embedded into policy in order to figure out what that revealed about the preferences—value judgments—that could impact who might get an organ and who might not in the match run. We wanted to determine what the balance is in current policies.

What did your analysis reveal?

Stewart: By applying this method, we found that the factor that most influences lung patients’ rank ordering on the match run is the proximity between the candidate’s transplant hospital and the donor hospital. We found that the lung allocation score (LAS) was second in terms of priority, followed by pediatric priority and then blood type.

Stewart: By applying this method, we found that the factor that most influences lung patients’ rank ordering on the match run is the proximity between the candidate’s transplant hospital and the donor hospital. We found that the lung allocation score (LAS) was second in terms of priority, followed by pediatric priority and then blood type.

What was the reaction to how heavily proximity is currently weighted in lung policy?

Alcorn: Many folks were shocked to see how heavily it was weighted. A lot of people know that geography and distance play a heavy factor in allocation now, but to actually quantify it, this was the first time we were able to put a number on it like this.

Alcorn: Many folks were shocked to see how heavily it was weighted. A lot of people know that geography and distance play a heavy factor in allocation now, but to actually quantify it, this was the first time we were able to put a number on it like this.

Video

Understanding continuous distribution

How is continuous distribution different from the current system?

How does the points-based system work?

De-mystifying the points-based approach to organ allocation

A recent study by UNOS researchers demonstrates how a flexible points-based approach to lung allocation policy has the potential to make better use of the limited supply of donor lungs.

What is AHP?

Goff: Analytical hierarchy process (AHP) is another method that the committee has leveraged to help prioritize decisions during the lung allocation process. It helps answer complex questions and is one of the most frequently used tools in multi-criteria decision making. We were lucky enough to work with some of the experts in this field who are also experts in working with patients, or non-professionals, and using AHP to make clinical decisions. What it does is it asks you, in a more direct way, which is more important? What are your values? We were able to use it to collect information from the community about what different demographic groups value.

Goff: Analytical hierarchy process (AHP) is another method that the committee has leveraged to help prioritize decisions during the lung allocation process. It helps answer complex questions and is one of the most frequently used tools in multi-criteria decision making. We were lucky enough to work with some of the experts in this field who are also experts in working with patients, or non-professionals, and using AHP to make clinical decisions. What it does is it asks you, in a more direct way, which is more important? What are your values? We were able to use it to collect information from the community about what different demographic groups value.

How have non-clinicians been involved?

Goff: Using AHP was a new way to collect community input early in the process—it has allowed us to be really transparent about the impact of that input on the final proposal that will go out for public comment. We really wanted to make sure that the community could be involved in the process of designing continuous distribution, that stakeholders beyond the OPTN Lung Transplantation Committee could understand it. We explored other multi-criteria decision making methodologies, but elected to use AHP because it’s inclusive: it’s user-friendly for a patient family or a donor family. It’s not just for clinicians.

Goff: Using AHP was a new way to collect community input early in the process—it has allowed us to be really transparent about the impact of that input on the final proposal that will go out for public comment. We really wanted to make sure that the community could be involved in the process of designing continuous distribution, that stakeholders beyond the OPTN Lung Transplantation Committee could understand it. We explored other multi-criteria decision making methodologies, but elected to use AHP because it’s inclusive: it’s user-friendly for a patient family or a donor family. It’s not just for clinicians.

Has a mixed-method approach to policy-making been taken before?

Stewart: I don’t think so, either internationally or in the U.S. It evolved out of our brainstorming in an exploratory phase where James had had some experience with AHP, and I had exposure over the years to the discrete choice type of experimentation. As we just kept moving forward, we said wait a minute, the match-run data has the current policy’s ‘preferences’ built-into it, right? The patient that’s ranked first, compared to second or third or fourth—that ordering reveals the inherent preferences baked into the policy, and we can use math to summarize all of the data in a meaningful way.

Stewart: I don’t think so, either internationally or in the U.S. It evolved out of our brainstorming in an exploratory phase where James had had some experience with AHP, and I had exposure over the years to the discrete choice type of experimentation. As we just kept moving forward, we said wait a minute, the match-run data has the current policy’s ‘preferences’ built-into it, right? The patient that’s ranked first, compared to second or third or fourth—that ordering reveals the inherent preferences baked into the policy, and we can use math to summarize all of the data in a meaningful way.

The methodology basically looks at the characteristics of the patient ranked first, and then says, ‘Well, there’s a value judgment there compared to all the other patients on the list.’ Then it looks at the patient ranked second and says, ‘Okay, what are the characteristics of that patient compared to everyone else further down?’ And then the third versus everybody down. It just absorbs all that information to summarize it into a fairly simple formula.

How is the team using big data?

Goff: The Revealed Preference Analysis looked at match run data over multiple years. Multiply a couple of years’ worth of more than 6,000 matches, with thousands of candidates in each and you’re definitely working with a big data set to analyze and model.

Goff: The Revealed Preference Analysis looked at match run data over multiple years. Multiply a couple of years’ worth of more than 6,000 matches, with thousands of candidates in each and you’re definitely working with a big data set to analyze and model.

Stewart: Each data point represents more information that the statistical model has to work with in estimating the influence of each attribute on patient rank-ordering. The more data points, the more confidence we have in these estimates.

Stewart: Each data point represents more information that the statistical model has to work with in estimating the influence of each attribute on patient rank-ordering. The more data points, the more confidence we have in these estimates.

How will continuous distribution transform organ allocation?

Alcorn: It’s an exciting moment for the OPTN not just because of the benefits that continuous distribution will bring as a policy, but also because of the increased equity it will bring for patients and the transparency it demonstrates for the community in the policy-making process.

Alcorn: It’s an exciting moment for the OPTN not just because of the benefits that continuous distribution will bring as a policy, but also because of the increased equity it will bring for patients and the transparency it demonstrates for the community in the policy-making process.

It’s also an exciting time because we are transforming how we develop these policies and what that means for future policy development.

![]()

“One of the big takeaways here is that UNOS is using analytical methodologies and leaning on experts with proven track records outside of transplantation to help us improve the transplant system.”

Darren Stewart, UNOS principal research scientist

Meet the team developing the new framework.

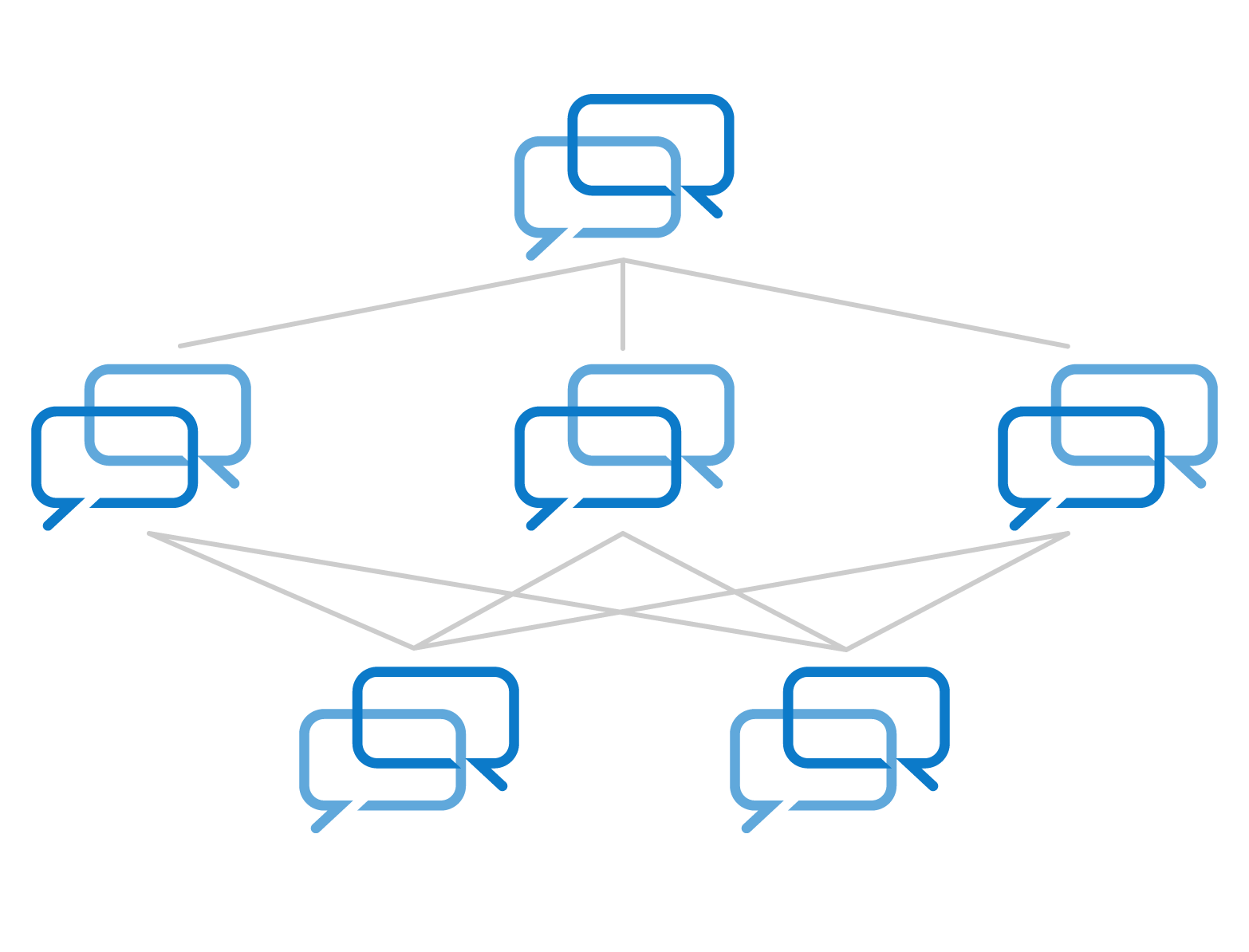

Lung is the first organ type to establish continuous distribution as its new framework for allocation. The work started with the OPTN Thoracic Committee in winter 2019 and has been continued by the OPTN Lung Transplantation Committee that was formed in summer 2020. Read how the committee is using input from the community to help design continuous distribution policies.

A more fair and flexible system for all organs

The OPTN plans to transition all organ systems to continuous distribution, but the lung community will be the first. Learn more about how the continuous distribution framework works, the timeline for implementation, and how it will create a more fair and flexible system for all organs.

What is the process for other organs to transition to continuous distribution?

Many decisions have to be made, involving multiple stakeholders and comprehensive research, to develop the new continuous distribution system and achieve improvements for the entire donation and transplantation community. Each organ specific committee will move through the same steps to develop a policy proposal that will open for public comment and be submitted to the Board for final approval. Learn more about the process for building the framework.

“By moving to the continuous distribution system, patients are going to benefit. We’re going to transplant patients in need more quickly by removing those hard boundaries that today sometimes prevent them from getting an organ.”

James Alcorn, UNOS senior policy strategist