Published Feb. 28, 2023; last updated March 17, 2023

Note: An outlet called The Markup, in partnership with The Washington Post, approached us with questions about the nation’s liver allocation policy, which has been in place for three years and has saved more of the sickest patients’ lives. In an effort to provide full transparency to our community, you can read our response below, provided to the outlet on Feb. 27, 2023. You can also review the letter we provided with our responses.

UNOS overview on the policy's impact

Relative to all your questions, we want to make one essential point at the outset: federal law, codified by HHS in 2000 in what is known as the OPTN Final Rule, requires that policies be designed to achieve equitable organ allocation by distributing organs over as broad a geographic area as possible and with the sickest patients being served first regardless of location.

In 2010, the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Organ Transplantation (ACOT) explicitly recommended the OPTN develop evidence-based allocation policies not determined by arbitrary administrative boundaries such as donation service areas (DSAs), OPTN regions and state boundaries.

And in 2018, HHS determined that “the OPTN has not justified and cannot justify the use of donation service areas (DSAs) and OPTN regions in the current liver allocation policy and the revised liver allocation policy approved by the OPTN Board of Directors (OPTN Board) on December 4, 2017, under the HHS Final Rule affecting the OPTN.”

In developing your story, we urge you to do so with federal law clearly stated and top of mind. Respectfully, your questions lead us to believe you already have determined that a number of institutions and individuals within the system colluded in or around 2016-18 to design an allocation policy that would redistribute deceased donor livers from poor states/areas to wealthy ones. You also appear to be selecting and analyzing data points in a vacuum.

We urge you, instead, to use the most complete/updated data rather than data that have been cherry-picked to support a pre-ordained conclusion. In our responses, we have either supplied that data or provided a source for them.

We cannot emphasize enough how complicated, evolutionary, and carefully considered is the process of developing policy for allocating organs as equitably as possible. As we have just demonstrated, federal law has consistently come down on the side of giving precedence to patients over place. Every single volunteer sitting on every OPTN policy committee takes their responsibilities very seriously and approaches policy discussions from a particular perspective. Not all are in agreement and feelings run strong on the subject of acuity circles. But ultimately and over time, the OPTN Board of Directors must comply with federal regulation, even as constant analysis is undertaken by the OPTN to assess how well organ allocation policies are working for the entire system. This is done, not with a particular bias toward some states over others, but to ensure the most patients are best served across the widest possible area without regard to location.

To that end, it is also important for you to objectively assess and report the system’s findings that, at the two-year mark, the new liver policy appears to be working as intended for the broadest number of patients who are the sickest, no matter where they reside.

Assessing the liver policy in isolation, using incomplete or outdated data that supports a narrative not in any way consistent with the more expansive picture, undermines not only years of work to develop a liver policy that complies with federal statute, but potentially interferes with unbiased, agenda-free analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of all related OPTN policies.

Your reporting may be accepted by readers as fact. Treating the controversy over the liver allocation policy in isolation and characterizing it as a turf war between wealthy and poor states in which wealthy states have won would be a gross misunderstanding of the framework in which all of the OPTN’s policy work is conducted on behalf of all transplant patients. It would not only be a disservice to your readers, but to those waiting for organs, to the entire system, and – critically – to the intent of the law, which demands equity for the sickest patients irrespective of where they live. Extremely sick people depend on the most equitable system possible and if those in the media or political sphere assess it with anything other than the most complete and comprehensive data – and an open mind about interpreting such data– they risk putting these lives in jeopardy.

With the system’s comprehensive framework and goals established, we would also like to address some specifics:

- The liver allocation policy is designed to help transplant candidates of any age, not adults only. In fact, the policy goes to great lengths to aid children as well as adults and accounts for the differences in their medical needs. Our responses will address transplants for all candidates and recipients, regardless of age.

- We want to be sure you’re aware that full-year 2022 data is available on the OPTN website and has been since early January. This will allow you to advance your analysis of the policy well beyond 2021, which is where your comparison currently stops. In addition, your statistical comparisons will be more rigorous and relevant if, instead of comparing results over two specific and isolated years, you instead use the very detailed monitoring reports available to look at entire cohorts of outcomes before and since policy implementation. The most recent of these monitoring reports covers two-year periods of activity before and after the policy took effect, In a number of instances, this two-year monitoring report, which has been available on the OPTN website since August 2022, addresses your findings and reaches different conclusions. We are happy to address your questions if you are interested in understanding why this might be the case.

- A known issue affecting any pre- and post-policy analysis is that the acuity circles liver allocation policy took effect very shortly before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have acknowledged this fact in all policy monitoring reports; however, the unprecedented nature of the pandemic has limited our capacity to fully characterize post-policy outcomes in the same way as in the pre-COVID era. In general, we know that the pandemic has had many effects on whether and when transplant candidates have been listed, whether candidates were inactive at the time of organ offers due to COVID infection, and whether some transplant candidates or recipients died of COVID infection. In addition, COVID had differing effects on healthcare access in different states, and often at different time frames from 2020 to the present. Varying access to urgent and intensive care in various parts of the country during COVID outbreaks has had a real but unquantifiable effect on transplant access at different times.

In general, the monitoring reports have noted the following findings or supported the following conclusions:

- Deceased donor liver transplants increased by more than four percent nationwide in the first two years of the acuity circles policy.

- Liver transplant rates increased significantly for the most medically urgent candidates. This was an outcome specifically intended and expected.

- Waiting list removals either for “patient death” or “patient too sick to transplant” decreased – again a result consciously intended and expected.

Fact-based assessment of the policy and its development

Find The Markup’s questions and assumptions and our own responses, in addition to this letter that accompanied our responses:

“The policy is designed to provide the highest priority to individual liver candidates with the highest medical urgency, wherever they are listed in the country.”

The Markup‘s statements and UNOS’ responses

1. The Markup

Fifteen states – Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Alabama, Texas, Kansas, North Carolina, Arizona, Iowa, Tennessee, Michigan, South Dakota, Wisconsin, South Carolina, Colorado, Mississippi – and Puerto Rico performed fewer adult liver transplants in 2021 than they did in 2019, despite transplants being up overall nationally. All but three of those states are located in the South and Midwest. Twenty-two states – New York, Florida, Oklahoma, Ohio, California, Virginia, Utah, Minnesota, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, Indiana, Oregon, Georgia, Nebraska, Connecticut, Hawaii, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Arkansas – and Washington, D.C. performed more liver transplants in 2021 than 2019.

UNOS

To reiterate, the liver policy is not operating in a vacuum and cannot be assessed in a vacuum. In each state cited, the new policy will be one of multiple factors potentially affecting a state’s transplant volume. For example, in any given state that has a transplant hospital:

- new transplant programs may open

- existing transplant teams may relocate to new hospitals

- existing programs may increase or decrease staff capacity for transplantation

- and/or some programs may either inactivate for a period of time or close entirely (this was particularly true during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and might be interesting for you to look into)

In addition to the effects of COVID-19 noted above, there have been major changes since 2020 to the process by which liver candidates may get exceptional priority for liver transplants for a condition such as liver cancer. All of these things and more can affect the number, and the medical need, of patients in any state who are listed for or who receive transplants at any given time.

Any serious statistical analysis should also attempt to identify whether, and to what degree, the change being studied may have a significant effect on a particular outcome, such as transplant volume. As addressed in the two-year monitoring report, a Kruskal-Wallis test indicated that there was not a statistically significant change from before to after the policy in the number of deceased donor, liver-alone transplants by the state of the liver transplant hospital for either adult (page 41) or pediatric recipients (page 64). This means that the differences observed in volume have no known relationship to the policy itself.

To put all of this in a larger context, a recent comparison, based on the two-year monitoring report, revealed that of the states with liver transplant programs, the majority had a difference of no more than 10 percent greater or fewer transplants after the acuity circles policy took effect. Of the states where there was a substantial change, more of them had a substantial increase than a decrease. Also keep in mind that percentage change is a function of overall volume. In areas where fewer transplants are done (such as South Dakota), a small numerical change may show a larger percentage change than in an area with larger transplant volume.

As a specific correction to your analysis with more complete data, the two-year policy monitoring report indicates that over the entire two-year post-implementation period, the state of Colorado performed more transplants than in the previous period (230 adult recipients and 10 pediatric recipients post-policy, total 240, compared to 218 adult recipients and 14 pediatric recipients pre-policy, total 232).

2. The Markup

As we look at the adult data, our conclusions seem to track with your findings. Could you please be specific about the portions of the two-year monitoring report that you mentioned reached different conclusions?

UNOS

As previously stated, UNOS evaluates the new liver policy’s performance based on whether it is succeeding in transplanting the sickest patients first regardless of geographical barriers. That goal, in accordance with OPTN regulations, is what drives 1) our approach and 2) questions we ask ourselves when analyzing relevant data.

That said, we do also examine the performances of individual DSAs, regions and states. However, in doing so we consider multiple variables before drawing conclusions, rather than just inspecting whether the number of transplants increased or decreased.

In order to answer your question as specifically as possible, we want to first walk you through our methodology:

What We Assess:

There are 40 states with a liver program (pediatric and/or adult). These are the ones we consider.

How We Assess:

In our data analyses, we set aside marginal increases or decreases in transplant of +10 percent or –10 percent.

Though obvious, it cannot be overstated that every registration on the organ transplant waitlist represents a real, suffering person whom this system works tirelessly to save. Our data practice relates to our ability to make meaningful determinations with respect to the fact that transplant programs across the U.S. vary in size and ability. For example, some transplant hospitals only perform surgeries for one or two particular organs; others may have smaller programs that perform only a few dozen surgeries per year. In both cases, a year-to-year difference of +/-10 percent or even fewer transplants can hinder effective evaluation if these factors are not taken into account during analysis.

What We Find:

When we compare all liver transplants, pre- and post-acuity circles policy, half saw a decrease in liver transplants. However, a decrease of 1 is different than a decrease of 100, so to put them all on the same scale, we examine states with more than a 10 percent change in either direction.

That leaves us with 21 states that had an increase or a decrease of at least 10 percent in total liver transplants within 2 years after the policy was implemented. It’s important to note that one of these states, Delaware only has a pediatric program of small volume; they experienced an increase in transplants from 7 to 10, which is a 43 percent increase.

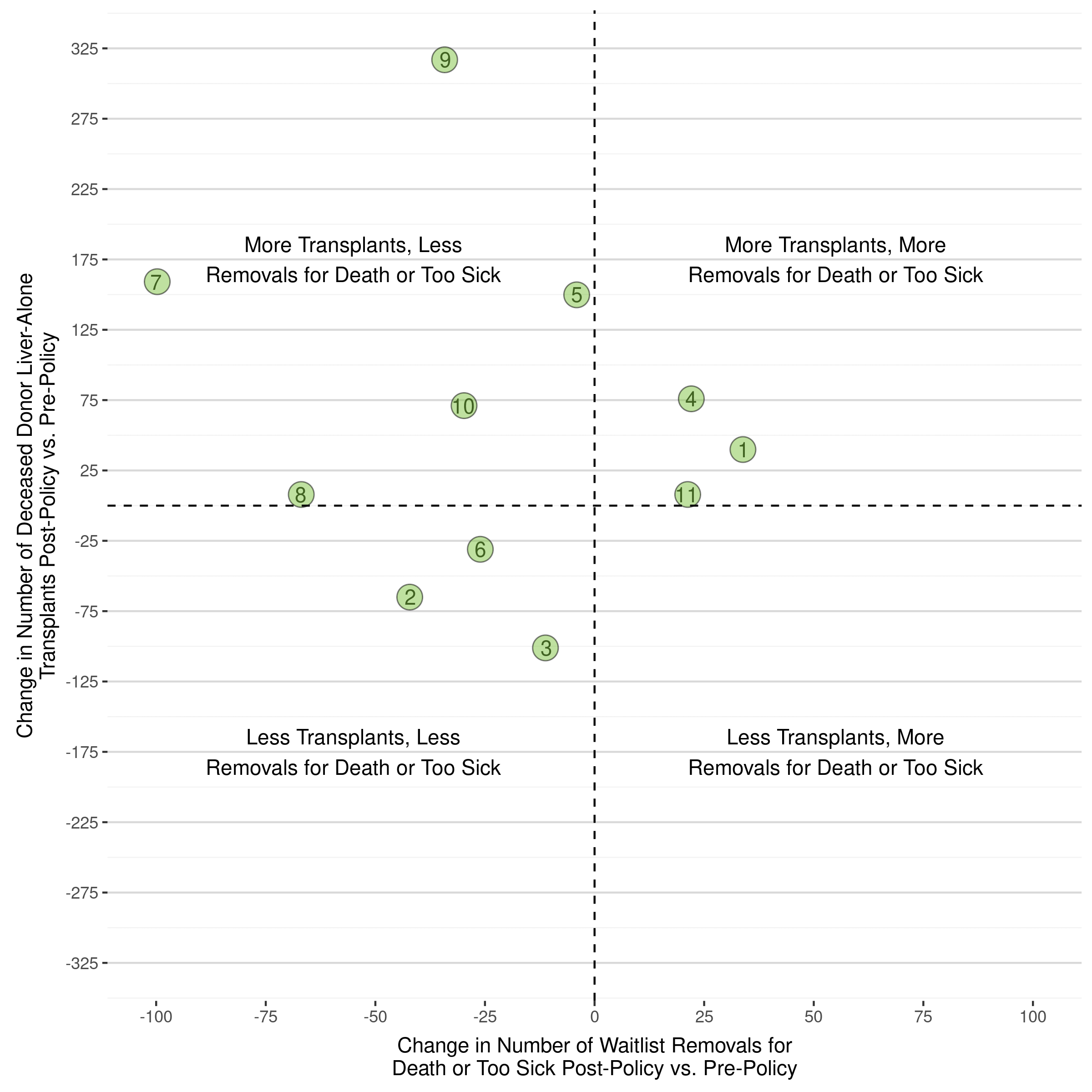

Excluding Delaware, the remaining 20 states with at least a 10 percent change in transplant volume (9 saw a decrease, 11 saw an increase), were located across the U.S.:

- 5 in the Southeast

- 2 in the Mid-Atlantic

- 2 in the Northwest

- 5 in the North Midwest

- 3 in the Great Lakes

- 1 in the Northeast

- 1 in the South Midwest

- 1 in the Southwest

Breaking this down further, of the 9 that saw a decrease:

- 3 were in the Southeast (Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana)

- 3 were in the North Midwest (Iowa, Kansas, South Dakota)

- The remaining 3 states with at least a 10 percent decrease were Indiana, Pennsylvania and Washington

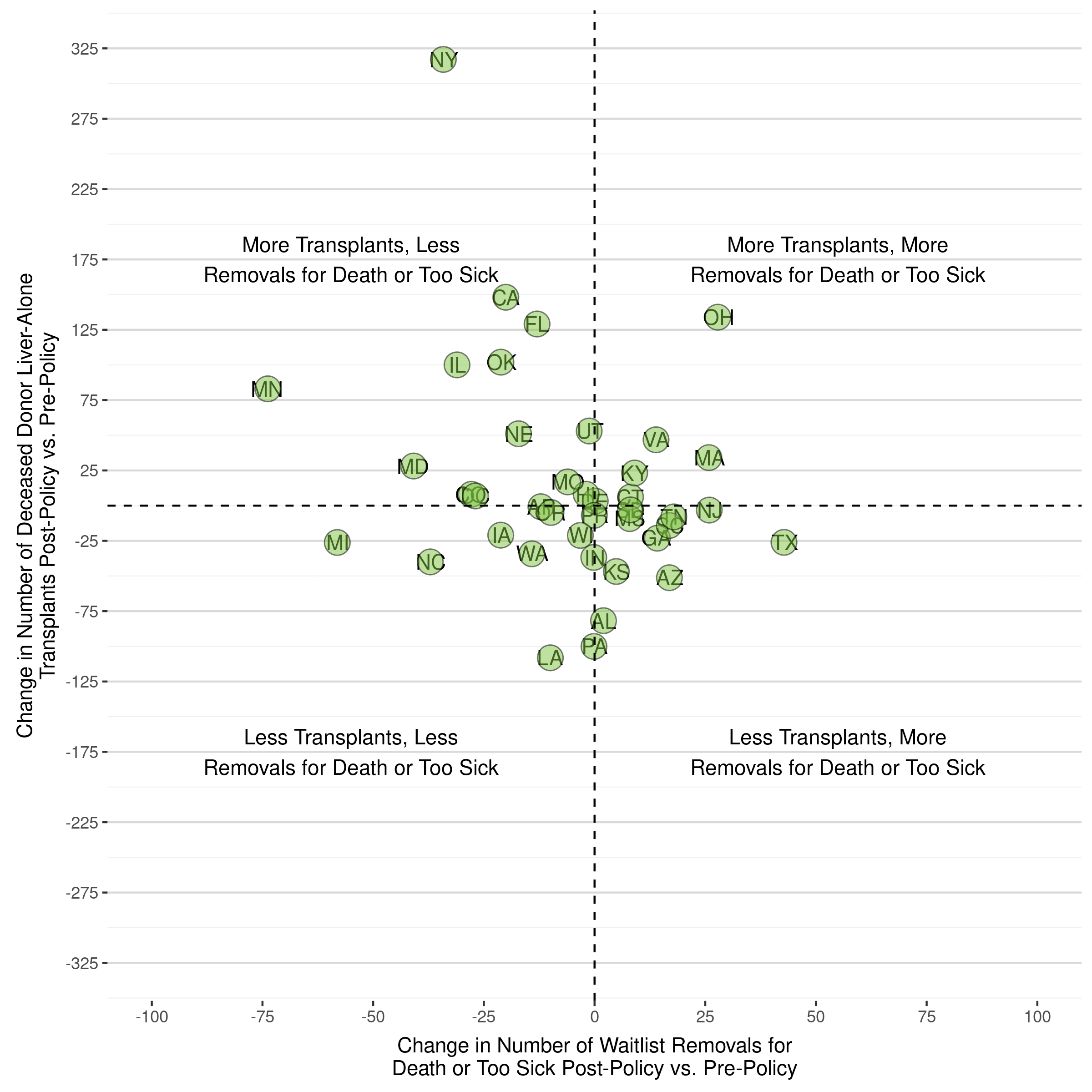

However, we consider the following important variable (among others) when assessing: Waiting list removals for death or too sick to transplant, which balances out the decrease in transplants performed.

When we do this, we see the following:

- Alabama, Louisiana, Iowa, and South Dakota all saw no-change-to-improvement in the number of waiting list removals for death or too sick

- Only Mississippi and Kansas saw more than a 10 percent increase in removals for death and too sick to transplant

Additionally and notably, Florida, Kentucky, Minnesota, Nebraska and Oklahoma, all of which are in the South and Midwest (we know this is your area of focus, which is why we highlight it) saw at least 10 percent increases in transplants.

Next Steps:

The way the OPTN policy development process operates is to let the pre-modeled policy take effect, assess its effectiveness over time in comparison to predictions, and then revise policy accordingly to enhance that which is working and fix that which isn’t working. We will do the same with the liver policy. We also predict the new continuous distribution allocation framework will positively impact the system’s goal of equity in all facets of transplant. This framework is very promising and we urge you to look into the opportunities it presents for improving the system overall, state-by-state, and across demographics.

Additional Variables:

From the two-year report:

Deceased Donor Liver-Alone Transplants – Page 41 – adult: “The majority of states had a similar number of deceased donor liver transplants post-policy compared to pre-policy. A Spearman’s rank correlation of ρ= 0.971 indicates a strong positive, monotonic relationship between these two measures. The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated that there was not a statistically significant change pre- to post-policy in the number of deceased donor, liver-alone transplants performed in each state (chi-square test=0.0924, p=0.761).”

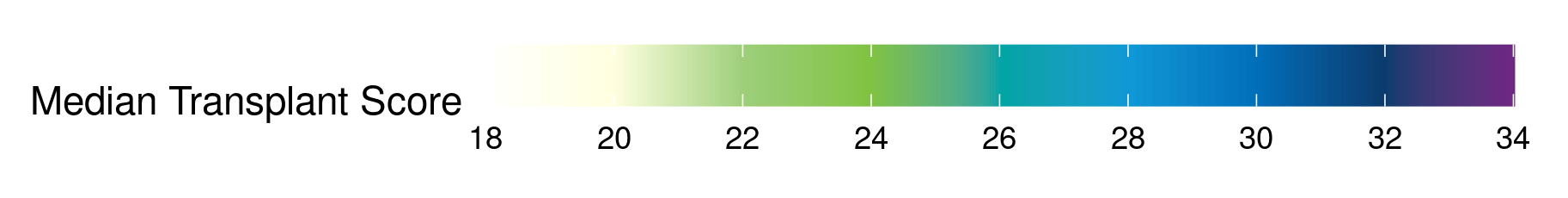

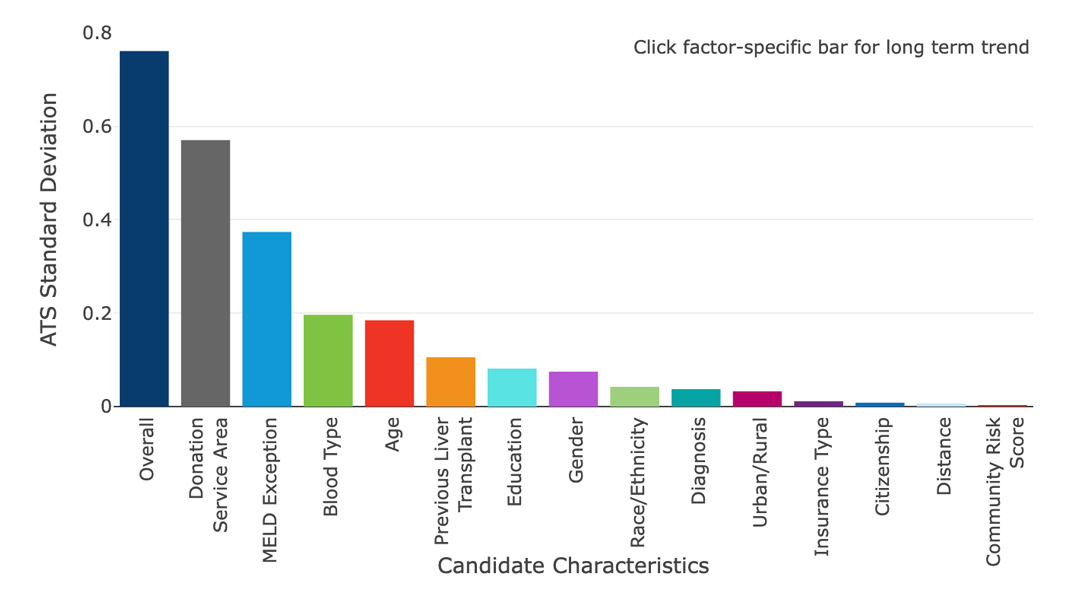

National Median Transplant Score (MTS) and Variance in MTS – Pages 54-55 of 2-year monitoring report: “However, within geographic units, the MTS distributions remained relatively similar pre- and post-policy.

It was also important to quantify the variation in median allocation MELD at transplant between different units. Changes in variance decreased post-policy by OPTN region, DSA, and state. Variance between transplant programs increased.”

Pediatric – Page 64: “The majority of programs performed similar number of deceased donor liver transplants pre- and post-policy. A Spearman’s rank correlation of ρ= 0.906 indicates a strong positive, monotonic relationship between these two measures. The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated that there was not a statistically significant change pre- to post-policy in the number of deceased donor, liver-alone transplants performed within each state (chi-square test=0.4764, p=0.49).”

Median Meld at Transplant (MMaT) – The intent of the policy was “..to address geographical variation in access to liver transplants”, meaning to equalize MMaT across the country – page 3: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2329/liver_boardreport_201712.pdf. States with higher MELDs pre-policy were expected to perform more transplants post-policy because patients listed in those states were sicker and more medically urgent (i.e. higher MELD). This was achieved – per the report, “…within geographic unit, the MTS distributions remained relatively similar pre- and post-policy. ….. It was also important to quantify the variation in median allocation MELD at transplant between different units. Changes in variance decreased post-policy by OPTN region, DSA, and state. Variance between transplant programs increased.” So, while the MMaT remained stable, the variance did decrease by OPTN region, DSA, and state, as intended.

General Information/Data:

As you can see, by factoring in statistical significance and applying highly relevant variables, we arrive at different conclusions from the ones you have drawn.

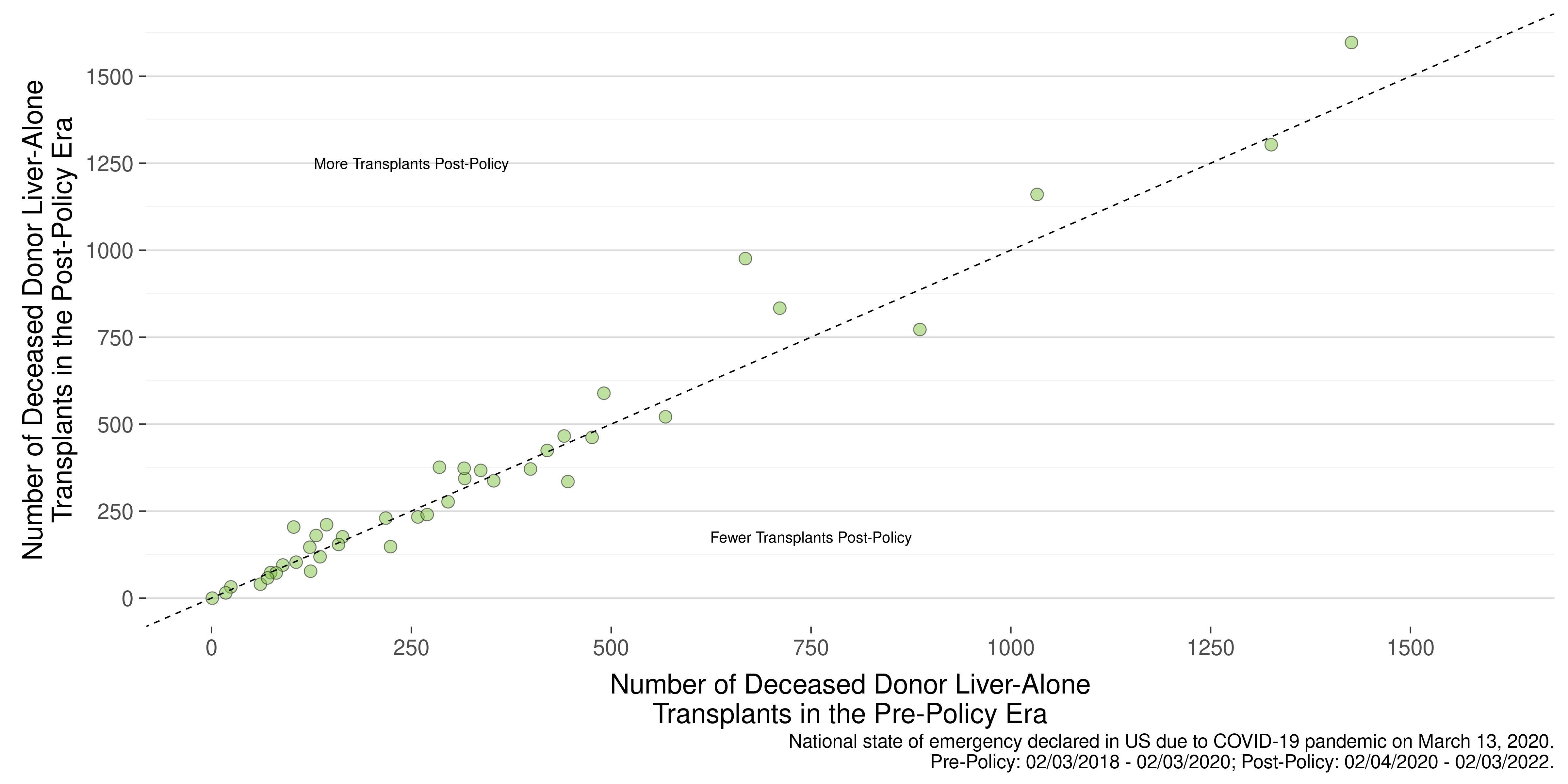

A solely quantitative focus on individual state volume misses the larger context of evaluating policy performance by a national system designed to serve all states equally and simultaneously. The below diagram from the two-year monitoring report shows the relative changes pre- to post-policy for all states with a liver transplant program. As in your analysis, it only compares liver transplants for adults. The individual states are not listed in this chart, as the point is to visualize the overall effect of the policy and the magnitude of change.

Figure 24. Adult Deceased Donor Liver-Alone Transplants by State and Era

The diagonal line indicates no volume change from pre- to post-policy. Any bubble (state) along that line essentially had no substantial change. Any values to the upper side had an increase in transplants; any below the line had a decrease. The farther from the line, the greater the degree of change. You will see that the vast number of states group along that line, indicating either no change in volume or no substantial degree of change. Where there are substantial degrees of changes, the greater changes tend to be increases (above the line) than decreases (below the line).

The same essential conclusion is expressed in a slightly different way in this article, which was shared with you earlier. Most states with liver transplant programs had a difference of less than ten percent greater or fewer transplants (and that percentage may also be affected more for states already performing lower volume pre-policy). Where there were substantial changes, more states were likely to see increases rather than decreases.

We cannot quantify every factor that may cause transplants to go up or down in a given area over time. We have addressed a number of those factors in this and other responses. However, any change in volume cannot be specifically associated with the acuity circles policy.

Visually, the below images show this information by both OPTN Region and by State. Importantly, there is no OPTN region, a collection of states in close proximity, that had less transplants AND more removals from the waiting list for death/too sick across all states comprising that region. While organs are not allocated by OPTN region any longer, they are also not allocated by state.

Lastly, we wish to restate that an analysis of a complex national system such as liver transplantation cannot be distilled into a single metric. If you choose to report on state level information, we recommend that you include additional metrics for each state in your analysis. For example, a state could perform fewer transplants in a given year (Table 87) but not see a decrease in deaths (Table 85). States such as Florida and Iowa are examples of this situation.

3. The Markup

Thank you for your response about factors that potentially affect a state’s transplant volume. If you have any examples of where those factors did impact a transplant program’s volume, please share those.

UNOS

In many instances, the potential impact will be in transplants not performed, or perhaps performed at a different hospital, thus not able to be monitored by the transplant program where the patient was originally listed. These are factors with the real potential to affect findings, particularly findings based on a non-continuous year-to-year approach instead of a full cohort-to-cohort review.

Examples of such events include the following:

- The pandemic had a huge impact on liver programs nationwide as well as differential impact in various parts of the country.

- For a broad overview, this journal article (https://aasldpubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep4.1620) details national effects in terms of organ recovery and transplant activity. Figure 2A in particular shows the significant disruption in liver transplantation in the early and middle months of 2020.

- Another such paper is here (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33244847/): Goff RR, Wilk AR, Toll AE, McBride MA, Klassen DK. Navigating the COVID-19 pandemic: Initial impacts and responses of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2021 Jun;21(6):2100-2112. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16411. In addition, liver transplant programs had the option to temporarily inactivate candidates who were either infected with COVID or were not considered to be in immediate need of a transplant. Effects differed by specific location and time. The week of March 15-21, 2020, liver programs in the South Midwest inactivated 59 candidates for COVID precautions. The following week (March 22-28, 2020), programs in the Southeast inactivated 61 candidates for the same reason. Both levels of inactivation were proportionally higher than inactivations in other regions at that time or afterward. These activities are documented under the “Waitlist” tab on a data dashboard established on the UNOS website in 2020 (https://unos.org/data/#Current).

In other examples, program inactivations (cessation of transplants without permanently closing) may occur at any time and may last short or long periods. As of March 1, 2023, four liver transplant programs are inactive (Broward Health Medical Center, Penn State Hershey MedicalCenter, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, and Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin). Candidates listed at inactive programs may choose to stay listed there, but they will not receive organ offers at that time. Or they may choose to transfer their listing to another program, which again may or may not be in the same metropolitan area or state.

4. The Markup

You mentioned that the two-year monitoring report identified ways that the acuity circles policy is “beginning to improve” equity in several ways. Please indicate what you are referring to in the report.

UNOS

A key measure of equity in transplant allocation is the amount of variance based on identifiable factors in the patient population. One of the major goals of the acuity circles policy is to reduce the variation in the median MELD/PELD score at transplant between transplant recipients in various geographic areas.

The executive summary of the two-year monitoring report (page 6) notes that the variance in median transplant scores has decreased for OPTN region, donor service areas (the area served by a particular OPO) and state. These changes have not yet achieved statistical significance, but we expect further reduction in variance over time.

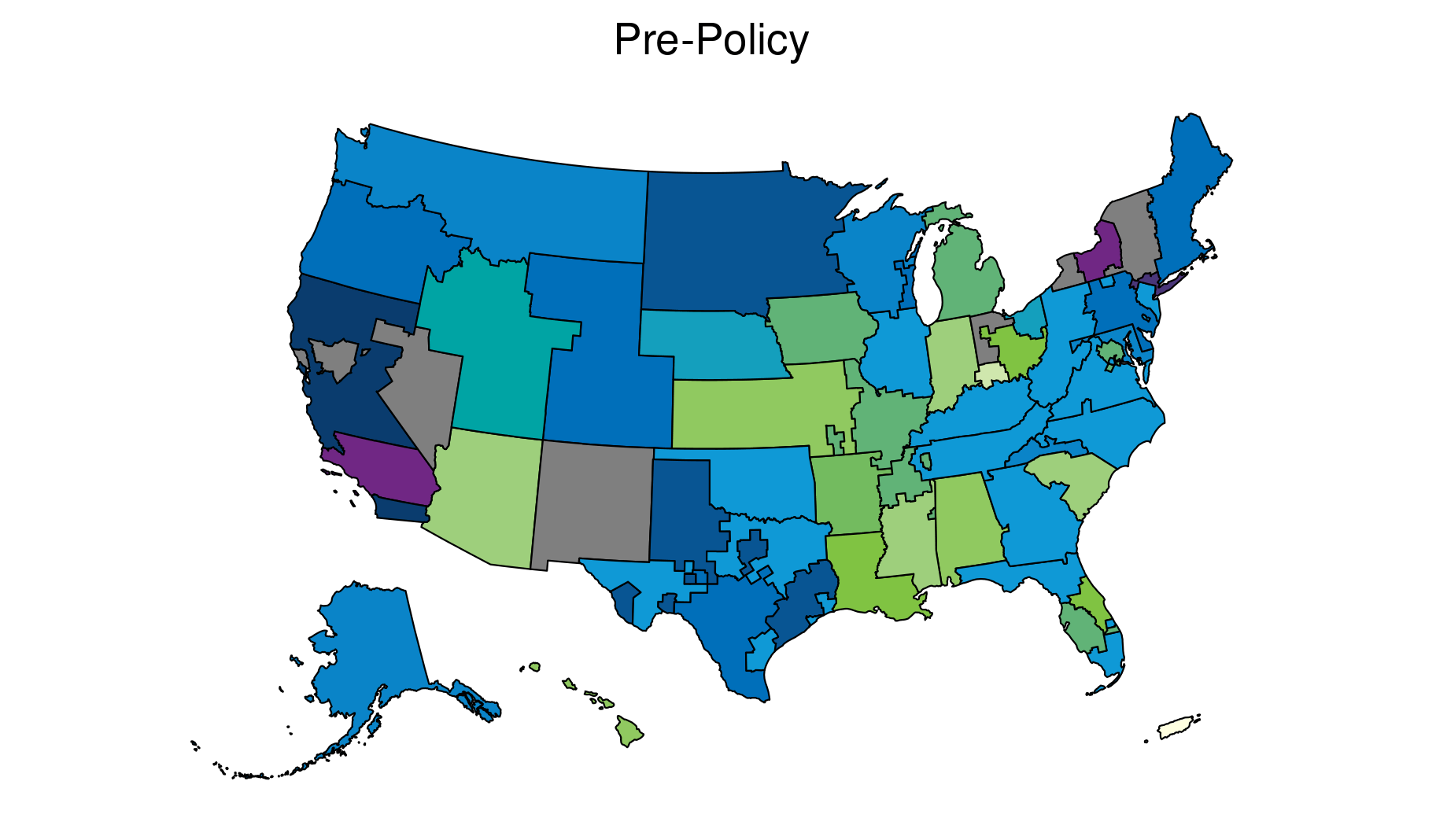

The “equity in access” dashboard for liver allocation indicates that the single factor that continues to create the most variation is the donor service area (DSA) in which the patient is listed. These are arbitrary geographic boundaries, and the current and future liver allocation systems are designed to counteract the effect of such artificial boundaries. You can view the equity in access dashboard here: https://insights.unos.org/equity-in-access/

Liver equity Dashboard

Variability in Access-to-Transplant Scores (ATS) among waitlisted liver candidates (04/01/2022 – 06/30/2022)

Further, the two-year monitoring report (Table 83) shows rates of transplantation increased for candidates identified as Asian, Non-Hispanic; Black, Non-Hispanic; Hispanic/Latino and Other.

Another important equity outcome is the reduction in removals from the waiting list due to death or being too sick to transplant. Those have been reduced post-policy, as was predicted by modeling of the policy in the development stage. (See discussion starting on page 16 of the two-year monitoring report.)

5. The Markup

New York, one of the biggest advocates of the policy change, saw the largest increase in adult liver transplants after the policy was implemented – 146 – with its transplants jumping by nearly a third from 2019 to 2021. California, where officials also were in favor of the change, also saw one of the largest increases during that time – 56 transplants – increasing six percent.

UNOS

The policy is designed to provide the highest priority to individual liver candidates with the highest medical urgency, wherever they are listed in the country. This includes candidates with the highest MELD or PELD score, which ranges up to 40 (the higher values are the most urgent). It also includes two statuses for highly medically urgent patients, Status 1A and Status 1B. These status determinations are based on objective medical information and are closely monitored to ensure that high-urgency patients are properly identified.

Any liver transplant hospital may have one or more highly urgent candidates at any particular time. But it is generally more likely for hospitals in areas with larger populations, such as New York and California (as well as in some other states such as Florida, Texas or Pennsylvania) to have a higher number of very urgent candidates and thus receive a greater number of liver offers for these patients. Again, a stated goal of the policy is to save as many lives as possible by directing livers first to patients in greatest need, regardless of where they are located.

As of 3:30 p.m. EST on Feb. 22, 2023, at liver transplant hospitals in California, there was one Status 1A candidate, six Status 1B candidates, and 18 candidates with a MELD or PELD score of 30 or higher. At hospitals in the state of New York, there was one Status 1A candidate, one Status 1B candidate, and 10 patients with a MELD or PELD score of 30 higher.

By comparison, at the same time and date in the state of Alabama, there were 3 candidates with a MELD or PELD score of 30 or higher, and no Status 1A or 1B candidates. In South Dakota there was one candidate with a MELD or PELD of 30 or higher, and no Status 1A or 1B candidates.

6. The Markup

Alabama saw one of the most significant decreases in transplants – 56 – with 2021 transplant numbers dropping about 44 percent from 2019. Another was South Dakota, which did six transplants in 2021, half of the number it did in 2019. Louisiana’s transplants during that period declined 27 percent, or 65 transplants.

UNOS

Our response can be inferred from the UNOS responses above.

7.The Markup

The states that performed fewer transplants have lower per capita household income than those that gained transplants. They also have lower insurance rates and fewer liver transplant hospitals per square mile. They face greater challenges affording care, qualifying for the list because of their ability to receive medical care prior, getting to and from appointments, and affording the surgery and post-transplant medicine. Critics of the policy say such issues put residents of these states at a disadvantage in accessing transplants already, and the new distribution of liver transplants under the acuity circles policy further unfairly disadvantages them.

UNOS

Within any state and among different states, individual access to healthcare varies widely. Access to transplantation is no different in this regard, just as access to many other specialized health services may vary within and between states.

The OPTN is required by statute to allocate organs to the individuals a transplant hospital has evaluated and added to the national transplant waiting list. The OPTN’s approach, shaped and dictated by federal law and policy, is to direct available organs first to the sickest transplant candidates and those who are the most compatible match with the donors. The guiding federal regulation states that the “candidate’s place of residence or place of listing” should not be a basis for organ allocation beyond any necessary measures to ensure a successful transplant. This is reflected in all organ allocation policies, including liver.

It should also be noted that not all people in a given state will also access transplant care in the same state. In fact, 10 states have no liver transplant program whatsoever, thus any potential transplant candidate residing there must seek care elsewhere. In many other instances, the closest or most preferred liver transplant program may actually be in a different state. This is especially true for residents of a metropolitan area that crosses state borders. Any analyses that are based on purely state-level results will miss these considerations.

Regardless, UNOS is very interested in how social determinants of health impact transplants. We assess, to the greatest degree possible, whether specific groups of transplant candidates may face differences in access to transplant once listed. Statistical modeling of the acuity circles policy, prior to its approval and implementation, indicated that the policy itself was unlikely to have a major effect on populations in different socioeconomic areas (rural, urban, metropolitan, etc.). While these effects cannot yet be studied in-depth based on the limited data available to us, we continue to seek additional data to inform these questions and continue to adapt policy accordingly.

Through the OPTN website, we also publish equity dashboards that display, for key factors, the level of disparity in transplant access among waitlisted candidates and whether the disparity has grown or shrunk over time. In the case of liver allocation, that variability has not increased under the acuity circles policy. That means that the policy has not diminished the equity of the system and is in fact beginning to improve it in some ways. Please see supporting data in the two-year monitoring report.

8.The Markup

You mentioned that the acuity circles policy modeling indicated that the policy was “unlikely to have a major effect on populations in different socioeconomic areas.” Minutes from the meeting where the policy was approved include comments from the audience raising concerns about the policy’s impact on various socioeconomic groups, and those in rural areas.

UNOS

It is crucial to understand that our comments about organ allocation policy modeling are in reference only to those patients on the transplant waiting list, not to populations as a whole whether socio-economically disadvantaged or otherwise. Patients on the waitlist nationwide is the population the policy was designed to impact, giving those on the waitlist who are the sickest priority in allocation regardless of where they live.

To reiterate, only patients added to the waiting list can receive organ offers, which applies for all organ types. The overall healthcare landscape in a given state, which varies widely, may impact who does and does not get added to the waitlist, but the liver allocation policy does not include oversight of or impact on state’s broader healthcare environment or the decisions made by individual transplant centers to list patients for transplant.

That said, once a patient is on the waitlist the policy prioritizes them based on how sick they are no matter what DSA, region or state they live in.

Here’s a hypothetical: A hospital is located in an area where there are 100 socioeconomically disadvantaged people who need an organ transplant, and 50 of those people are referred to a transplant hospital to be evaluated for transplant. The transplant hospital, for reasons of its own that have nothing to do with OPTN policy, accepts 25 of those people for transplant and adds them to the OPTN waiting list. Only those 25 people on the waiting list will receive organ offers, and in the order of the severity of their disease – applied consistently and without regard to geography. Therefore, organ allocation policies will not generate a disproportionately high number of organ offers to those 25 people on the waiting list simply because they live near a socioeconomically disadvantaged population . This would go against HHS’ federal mandate not to base allocation on DSA, regional or state boundaries. As stated previously, the OPTN system allocates organs to patients, not to geographic areas.

9.The Markup

We are also aware of a study from 2019 that found public preference for keeping donated organs locally when they come from areas with higher donation rates. Please see here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30582275/

UNOS

The corresponding author of the survey you mention is Dr. Seth Karp, whom you have previously noted is a strong critic of the acuity circles policy. He is also director of the liver transplant program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and three of the study coauthors are affiliated with Vanderbilt University. These authors cite “no conflicts of interest” to the journal where the article appeared, despite the fact that in the same month of its publication, Vanderbilt became a plaintiff in litigation regarding the acuity circles policy. Vanderbilt alleged in its suit that it would perform 220 fewer liver transplants over a 5-year period under the acuity circle policy, resulting in an economic impact to Vanderbilt of nearly $200 million. (Callahan et als v. HHS and UNOS, N.D. Ga, Case No. 1:19-cv-01783-AT, ECF-1 at para. 175).

In addition, the survey instrument first asks questions related to how respondents felt about organs being allocated to non-citizens. These questions were asked prior to questions about local residency. The issue of organ transplants to non-citizens, although not directly related to the acuity circles policy, is known to evoke strong feelings within the public. It may have had the effect of pre-conditioning the respondent to have in mind the non-citizen when asked, later in the survey, about whether they prefer to keep donations within the “same community” as the donor. Such pre-conditioning in survey development is known as “push polling.”

Finally, the survey you cite indicates responses from 102 participants. Statistical methodology indicates this sample size would have less power to drive larger conclusions about attitudes held by a broader population as compared to a sample size of 10,000 participants, which was indicated in the 2019 Gallup survey cited (Appendix A: Methodology).

10. The Markup

The states that performed fewer transplants also have higher rates of liver disease than those that benefited from the change. New York, for example, had the second-lowest rate of liver disease in the country in 2021, while Alabama, for example, had nearly twice the rate of New York and was in the top third in the country, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

UNOS

Your question assumes that every individual with liver disease is a transplant candidate. In fact, the incidence of any particular broad form of disease may not match closely to the number of people for whom a transplant is an effective treatment. This is particularly true with liver disease, which can occur in many forms, with different severity and prognosis, and for which there are a wide range of treatment options. In just the last few years, highly effective drug treatment for hepatitis C has vastly reduced the number of liver transplant candidates and recipients with this diagnosis.

In addition, as noted earlier, allocation policies are designed to match donated organs to candidates that a transplant hospital has evaluated and accepted for a transplant. Federal regulation states that the “candidate’s place of residence or place of listing” should not be a basis for organ allocation beyond any necessary measures to ensure a successful transplant.

The OPTN does not allocate organs based on overall end-stage organ disease burden in any given area. Policies are designed to allocate to those patients with end-stage organ disease who have been registered on the waiting list. In other words, in order for the OPTN to help a patient, they must be registered on the waiting list by a transplant hospital.

Continuous distribution, which eliminates circles entirely, is expected to be the system’s next major advancement in achieving even greater equity in organ allocation.

Another step the OPTN is taking is to seek authorization to collect additional data to help identify barriers to equitable waitlist access for patients with end-stage organ disease. This in turn can help us further develop policy that increases the number of patients nationwide who get onto the waitlist and benefit from transplant.

11. The Markup

Which diseases that cause end stage liver disease wouldn’t benefit from a transplant and are geographically clustered in a way that would affect these numbers?

UNOS

Many factors can contribute to doctors determining that a patient with liver failure isn’t a candidate for the transplant waitlist, most of them systemic comorbidities complicating or contributing to liver disease. Some examples include people who:

- are active alcohol or drug abusers

- have other serious illnesses

- have aggressive cancers (melanoma, lymphomas, bile duct cancer, etc.) in addition to liver failure

- have severe, untreatable disease in other organs of the body, such as heart or lungs

- have severe organ disease due to diabetes

- are severely obese

- have severe or uncontrolled infection, such as HIV or hepatitis B, that do not respond to treatment

- have severe autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or multiple sclerosis

- have a diagnosis of portal vein thrombosis (PVT), a disease of the vascular system feeding the liver

These types of comorbidities are so diffuse and common across the country that we don’t know of any liver diseases for which transplant is not indicated that are “geographically clustered.”

12. The Markup

The South and Midwest have higher rates of organ donation per capita than other areas of the country. Transplant professionals there have said that it’s not fair that states with poor procurement performance, such as New York and California, are receiving more livers under this policy at the expense of patients in the South and Midwest.

UNOS

The American public overwhelmingly supports organ donation and transplantation, and stories abound of heartfelt situations in which a donor from one part of the country becomes the gift of life to someone from another part of the country – often a person with a completely different life experience. These are stories of nationwide unity. Rarely are they divisive or contentious. In fact, donor families tend to be grateful that their loved one has saved a life, perhaps several, and do not care where these recipients are from, what they believe or what their backgrounds are.

Statistics support these stories of national commonality, and organs donated for transplant have often been referred to as a “national resource.” We are not aware of hard evidence or polling that people only care most about donating to someone in their immediate community. If anything, national polling indicates that a large majority of people prefer their lifesaving gift to help a person most in need rather than a local recipient (See National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices, 2019, Figure 18). This national attitude is entirely consistent with the goals and effects of the current liver policy.

We also have not seen any evidence that the preponderance of transplant professionals in the South and Midwest believe the liver allocation policy is not fair. Fourteen of the approx. 140 liver transplant programs nationwide sued to change the policy although half of those plaintiff hospitals are transplanting more livers under the new policy. This would seem a better gauge of sentiment than anecdotal opinion.

That said, the OPTN Board and its committees – which are comprised of transplant professionals, OPOs, donor hospitals and transplant center representatives, patients, donor families and more – exist to continually assess and increase organ donation and recovery from all eligible donors. We recognize and pursue opportunities for improvement in all areas of the country. We actively support collaborative efforts to enhance identification of potential organ donors and increased utilization of organs from those donors to the benefit of patients nationwide.

13. The Markup

States across the country are exporting more organs than before the policy. Twenty-two states exported a majority of their livers in 2019 – about 42 percent of all states and territories that exported organs. That nearly doubled by 2021 when 42 states did – about 80 percent of all states and territories that exported organs.

UNOS

By definition, 10 states (Alaska, Idaho, Maine, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Rhode Island and West Virginia) will export any liver recovered at a hospital there because they have no liver transplant program.

In other states, the “closest local” transplant program may be in another state, possibly not even a neighboring state. For example, the closest liver transplant hospital to a donor hospital in El Paso, TX, is in Tucson, AZ, not the other programs also in Texas. Again, this proves the sound logic of the policy and of federal legislation that drove the policy. Patients can access the closest hospital rather than one in their home state that might be farther away. We hope you’ll concur that the new policy is better for patients in communities like El Paso, who live closest to an out-of-state transplant center.

In other instances, under the previous organ allocation system with arbitrary and fixed boundaries, donor and recipient hospitals in metro areas that overlapped state boundaries may not have been able to share livers even as short a distance as 10 or 15 miles. In the New York City metro area, Manhattan was not only in a different local area than Newark or Hackensack, but an entirely different OPTN Region (the next level of allocation beyond local). Now that these arbitrary boundaries have been eliminated as a unit of distribution, it is absolutely expected that more organs will be transplanted outside of the state lines in which they were recovered.

Organs exported from any one area are correspondingly imported by another. In some instances, transplant programs and the patients they serve now have increased access to organs that can travel only a short distance despite coming from another state. For example, St. Louis is near the junction of five other states that are served wholly or in part by other OPOs.

14. The Markup

Livers are now traveling nearly twice as far as they did pre-policy – a median distance of 163 miles in 2021, as compared to 85 miles in 2019.

UNOS

We believe the important question isn’t whether more miles are being traveled but whether more lives are being saved, particularly among the sickest patients without regard to geography – the intent of NOTA and the OPTN Final Rule. Relative to the liver policy, the two-year monitoring report shows that more lives are being saved nationwide.

Furthermore, technological advancements have rendered the problem of distance between organ donor and recipient less and less a factor. This is a good thing, not a bad one. For example, we now have perfusion devices that act as mini-intensive care units for organs, allowing them to be repaired and remain viable longer outside the body. We also have GPS tracking systems. The system’s ability to transport over greater distances while maintaining organ viability is a win-win for donor hospitals, transplant centers and patients regardless of where they live. For example, today, a donor with a rare blood type will have a much wider pool of potential matches than before, thanks to both innovation and the removal of arbitrary geographic boundaries from factors determining allocation.

However, with regard to your statement, please note that the most recent data publicly available demonstrates that travel distance and time have not increased universally for all or nearly all liver offers. In fact, it has been reduced in some cases.

Data from the two-year monitoring report (Figure 38 – page 60) shows the median distance traveled increased from 72 nautical miles in the two-year pre-policy period to 141 nautical miles in the two years after policy implementation. This was an expected outcome of broader sharing, as the most urgent transplant candidate is not always at a transplant hospital close to the donor hospital.

The distribution charts in the report indicate that while 141 nautical miles is the statistical midpoint, that means half of individual liver offers travel a shorter distance (for example, 50 miles) than longer distance.

Another observation from the report is that it has become more common for livers to travel a distance between 250 and 500 nautical miles. This was expected, particularly given the policy’s emphasis on transplanting urgent candidates. But it also resulted in fewer livers traveling 500 nautical miles or farther, specifically for adult liver recipients. This is shown in Figure 36/Table 32 (page 57).

Finally, the report notes that even with an increase in median travel distance for liver offers, this has resulted in an increase in the median liver preservation (cold ischemia) time of only 10 minutes for adult recipients and 27 minutes for pediatric recipients. This small increase is not likely to affect the viability of most organ offers and has no observable effect on overall post-transplant survival.

We are continuing to develop a future liver allocation policy based on continuous distribution. In that system, the distance from donor to recipient hospital would still receive some weighting, but there would not be fixed allocation boundaries even in circle form. Other weighting could potentially address issues voiced by some in the community, including some assessment of healthcare access or disparity. This system is still in its formative stage, and we are currently seeking public input on its development.

15. The Markup

How many of the mini perfusion devices are used for livers? How widely used are they, and how long have they been that widely used?

UNOS

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first ex situ perfusion device on September 28, 2021. Prior to this, the use of perfusion devices was limited to the clinical trial setting. Currently, there are two machine perfusion devices approved by the FDA – Organ Care System (OCS) Liver and OrganOx metra – one pending FDA approval, and one in the clinical trial phase.

Here’s a good overview of the history and status of liver perfusion devices in the US and why they are poised to have an impact on the increase of livers available for transplant in the US.

You can learn more about transplant programs or OPOs currently using these devices by contacting the manufacturers of the two devices that have received FDA approval. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no publications as of yet examining outcomes of machine perfusion beyond the clinical trials for the already-approved devices. At this time, the OPTN does not collect data on the use of machine perfusion devices.

16. The Markup

I see you are in the public comment phase for changes to the policy, and it notes that the request for feedback is not a proposed policy change. Do you currently have plans to include an assessment of healthcare access or disparity in a liver allocation policy?

UNOS

Specific to the public comment phase for continuous distribution, the OPTN’s request for feedback is at a conceptual stage, not at the point of a policy proposal. We take this same methodical approach to all policy development. The OPTN continually seeks additional data and comment that will inform policies it is developing to improve issues of healthcare access.

17. The Markup

Organ procurement organizations in places without major airports say the increased travel is problematic for them, as finding a private plane on short notice can be difficult.

UNOS

Organ procurement organizations work on a daily basis with transplant hospital staff to arrange for effective organ placement. In some areas of the country, and at some times (such as during storms), the travel challenges may be greater than in other instances. As always, OPOs will seek needed and sometimes creative arrangements to make transplants happen.

UNOS is advocating for changes to help streamline transportation solutions and ease that burden, such as working with federal stakeholders to reduce the challenges associated with commercial air travel.

18. The Markup

More livers were discarded in 2021 than before the policy – 949 total – up about 9 percent from 2019. Critics of the policy said the increased travel time is partly to blame for the uptick.

UNOS

The following is from the two-year report: “Discard rate is defined as the number of livers not transplanted over the number of deceased liver donors recovered for the purposes of transplant, multiplied by 100 to get a percentage. Nationally the liver discard rate went from 9.0 percent pre-policy to 9.5 percent post-policy. Changes in discard rates by OPTN region continue to differ.” The change in the discard rate post-policy is +.5 percentage points.

Put a different way, the number of livers recovered increased 5 percent under the acuity circles policy. Livers not used increased 11 percent. However, when comparing all of the outcomes (including additional transplants), the overall rate of livers not used increased only slightly, from 9 percent to 9.5 percent. This means that the overall non-utilization rate largely did not grow at a faster rate than the growth in the number of livers actually transplanted.

19. The Markup

Seeing as the time period that we measured is different from yours, please share the most recent version of the 2022 discard data or monthly discard totals for all of 2022.

UNOS

Please see below for the liver non-utilization rate, by year, from 2019 through 2022. Per OPTN policy 18 (see page 319), Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs) have 60 days to submit Deceased Donor Registration (DDR) forms, in which organ disposition codes and organ non-utilization reasons are captured. When an organ disposition of ‘Recovered for Transplant but Not Transplanted’ is selected, a non-utilization reason must then be selected. There is a lag at the end of a year before non-utilization rates for that year can be accurately reported.

Liver non-utilization rate by year

- 2019: 9.6 percent

- 2020: 9.3 percent (policy implemented in Feb 2020)

- 2021: 9.9 percent

- 2022: 9.8 percent

Concurrently with increasing non-utilization, the US has also seen an increase in more medically marginal donors. Specifically, donation after circulatory death (DCD) has been on the rise alongside more traditional brain death donors (DBD). You can imagine that someone who had died suddenly and usually tragically – such that their brain no longer functions but their other organs are in tact – would have healthier organs than someone who has died after their circulatory and respiratory functions have stopped.

In the two-year report, it’s noted that, “There were 1,178 DCD transplants pre-policy and 1,585 DCD transplants post-policy. The majority of DCD transplants occurred for recipients with MELD scores of 28 or lower.” (Figure 32). While a greater number of patients are benefitting from an expanded donor pool, some organs from these more marginal donors are being recovered but ultimately not used for transplants. Additionally, more donors are being recovered from older age groups, specifically 50+, across both DBD and DCD donor types. We have noted that transplant centers are less likely to accept organ offers from DCD and/or older donors. However, the fact remains that these efforts to recover the greatest number of organs possible have resulted in improved transplant opportunities for more transplant candidates than ever before.

DCD and DBD donors recovered by year

- 2019: 2,718 DCD donors recovered, 9,152 DBD donors recovered

- 2020: 3,224 DCD donors recovered, 9,364 DBD donors recovered

- 2021: 4,190 DCD donors recovered, 9,673 DBD donors recovered

- 2022: 4,777 DCD donors recovered, 10,127 DBD donors recovered

Donors age 50+ by year

- 2019: 4,309 donors age 50+

2020: 4,545 donors age 50+

2021: 5,254 donors age 50+

2022: 5,791 donors age 50+

Any analysis of the percent of organs recovered for transplant and not ultimately transplanted leads to the question “why?” For each of these organs, the OPTN collects from the OPO a single reason for non-utilization.

Overall, the most commonly reported reason is “No recipient located – list exhausted” with 50.6 percent of non-utilized organs reported for this reason in 2022. Currently there is no reason in the list of options specific to transportation and logistical reasons, but there is a choice of “other, specify” to be used in instances where none of the listed reasons are applicable. During 2022, “other” was chosen 14 percent percent of the time, and in these cases additional text is provided to describe the reason in more detail. A manual review of this field identified very few organs indicated as being not utilized due to transportation or logistical issues.

Other metrics used to measure success in the transplantation of all available usable organs include:

- The total number of organs transplanted for each organ type

- The number of organs transplanted per donor (yield)

- The metric used by CMS to measure OPO performance, which looks at the number of organs transplanted per the number of deaths meeting specific criteria

As previously stated, we have noted that both the rise in non-utilization and in the number of organ transplants performed each year coincide with increased recovery and offers of more medically complex organs. The net number of patients who benefit from transplants continues to increase and can be driven even higher by further examining and addressing reasons for offer refusals by transplant hospitals.

20. The Markup

Patients’ survival rate also dropped to 92.8 percent from 94 percent during the first year-and-a-half of the change according to a report.

UNOS

The report cited for this question is outdated. The updated two-year monitoring report presents different findings: one year survival was 93.5 percent survival pre-policy and 93.1 percent survival post-policy (Table 53).

It is crucial to keep in mind that a major goal and achievement of the policy is to transplant the sickest, most urgent patients first rather than letting the sickest die if they are not in the right geographic region for an available liver. While liver transplant professionals are very skilled at managing their patients’ post-transplant outcomes, it is not intended but also not unexpected to see a minor reduction in overall post-transplant survival when a greater proportion of very sick patients are transplanted.

Over time, and as the most vulnerable patients are transplanted, we also hope to see a healthier population overall waiting for transplant, which can lead to survival rates actually increasing. This is why it’s valuable to look at the most recent data instead of data cherry-picked by critics.

21. The Markup

You said that as “more vulnerable patients are transplanted, we also hope to see a healthier population overall waiting for a transplant.” How does this work?

UNOS

Transplanting the most medically urgent candidates first also ensures transplant access for less sick candidates as well.

In the case of livers where the sickest patients have priority for transplant regardless of where they are located, once the most urgently ill transplant patients are transplanted, we logically expect a gradual decrease in how sick a patient will need to be to have sufficient medical priority for transplant, i.e. the median MELD score at transplant.

Here’s some background that hopefully explains why this makes sense:

When new allocation policies are implemented, there can be a transition period before the system stabilizes. During this transition period, patients who are disadvantaged in the older system and prioritized in the newer system will receive a greater share of transplants upon implementation of the newer system. This occurs because there is a build-up of these patients in the older system. As these patients receive transplants, this build-up decreases and the overall system recipients transition to its new normal – a list that is characterized by fewer desperately ill patients overall.

This is a known phenomenon that has been observed in previous allocation proposals. For example, this occurred with highly sensitized patients who received additional priority in the national kidney allocation system.

Our ultimate goal is to have organs available to transplant all patients when deemed appropriate by and in consultation with their physicians.

22. The Markup

While the acuity circles policy uses patients’ MELD score to determine who receives a liver, critics say the MELD score is not a perfect representation of a patient’s health because it does not account for comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes. Patients in the areas that saw a decline in transplants under the policy are more likely to be affected by conditions not captured by a MELD score that may cause them to be removed from the list because they are too sick or unable to withstand a transplant, according to transplant professionals there.

UNOS

Equitable transplant policies are a moving target as new data, insights and innovations come to light. Therefore, no transplant policy is set in stone. Federal policy demands equity to the fullest extent possible and does not expect – nor has it ever expected – the OPTN to implement acuity circles or any other policy and be done. The OPTN continually assesses policy effects and seeks to improve them.

In fact, within a few months we will implement a series of changes expected to improve the predictive ability of MELD, PELD, and the 1A and 1B statuses. We are also in the process of developing liver allocation based on the continuous distribution framework, which is predicted to further improve transplant equity as the law intends.

In addition, for any liver candidate for whom the transplant team believes their MELD or PELD score does not accurately reflect their medical need, the transplant team can apply to the National Liver Review Board (NLRB) and request a higher MELD “exception score,” which is the MELD score that the treating physician believes most accurately reflects the patient’s disease severity. The NLRB members are uncompensated volunteer peer clinicians, and they review all requests on an anonymized basis.

23. The Markup

Some members of the transplant community raised concerns about these populations during the policymaking process. Former UNOS CEO Brian Shepard dismissed their concerns in a private email, calling the concerns “an infuriatingly elitist argument masquerading as concern for the poor” and that “it’s a ‘give [transplants] to those of us who have to live near poor people’ argument.”

UNOS

As stated above, access to healthcare in general varies widely within and among the states, and access to transplant services reflects this broader disparity.

Any discussion of national importance, involving many different viewpoints, may spur heated observations made publicly or privately. To reiterate, the OPTN’s policy arm is driven by its federal mandate to make the system as equitable as possible for each patient, not for each DSA, region or state.

As stated earlier, UNOS has no financial interest in where any organ is allocated; UNOS’ primary goal is to transplant as many patients as possible.

On the other hand, 14 transplant hospitals placed their patients and programs ahead of the wellbeing of the nation’s patients and have spent $10 million+ in legal fees to the Jones Day law firm to maintain the status quo ante. Their goal was to avoid a negative financial impact of over $200 million per year that could have resulted from an aggregate reduction of 256 liver transplants annually. (Callahan et al v. HHS et al., N.D. Ga., ECF-1 at para. 179).

Since inception, half of the Callahan plaintiff hospitals are actually performing more transplants than they did before the acuity circle policy; responses to FOIA requests indicate that at least 3 of the public hospital plaintiffs have ceased funding this litigation.

24. The Markup

You mentioned that “UNOS’ primary goal is to transplant as many patients as possible.” Please explain how an increase in discards meets this goal.

UNOS

While discard increases are not ideal, they can increase at the same time transplants increase. The two-year report referenced above shows an increase in donors recovered for the intent of transplant from 17,898 to 18,834 pre- to post-policy. At this same time, total liver transplants increased from 14,646 to 15,278. Again, simultaneously, the liver discard rate increased from 9.00 percent to 9.51 percent.

Discards can increase for a number of reasons. One reason is that OPOs have begun offering more organs, including organs known as “marginal” that for clinical reasons might not be appropriate for every candidate. As OPOs offer more of these types of organs, one would expect that some of these organs would not be accepted. This, in turn, would increase the raw number of discards even as the number of transplants increases.

Additionally, individuals and transplant centers have varying acceptance behaviors; an organ that one surgeon will accept might not be accepted by another surgeon.

Further, acceptance behaviors at individual transplant centers can change over time as, for example, personnel changes and younger or more aggressive surgeons replace more risk averse surgeons. These behavioral differences influence where those organs are ultimately accepted and transplanted and whether or not they are accepted or rejected by transplant teams.

To drill down more specifically on the issue of marginal organs, an important factor in recent years impacting both transplant increases and discards is that more less-than-perfect organs are offered because medical advancements have increased their viability in general. This has created a situation in which the overall quantity of organs available has increased but the level of quality varies much more widely.

Furthermore, it is the right and responsibility of individual transplant teams, using their best judgement about a specific organ, to decide whether or not to accept it for their specific patient.

Consequently, the more marginal organs offered are at higher risk of being rejected by transplant teams, which may evaluate a less-than-perfect offer and determine it is not suitable for their patient. Ultimately, this marginal organ may end up being discarded because it has no takers. On the other hand, more and more of these marginal organs are being considered and accepted because studies of outcomes are showing they are working well for some patients.

This is how the system can experience a situation that seems contradictory but is in fact not contradictory; a simultaneous increase in both organ transplants and organ discards.

25. The Markup

Federal cost reports filed by 41 organ procurement organizations showed an increase in travel costs since the rule changed for 18 of the companies. The largest came from New England Organ Bank – a $1.5 million increase, up 160 percent, as well as Pennsylvania’s Gift of Life Donor program – up $1.2 million, or 86 percent.

UNOS

The OPTN does not collect or review OPO or transplant hospital cost reports. This is the purview of the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). However, with record numbers of donors and transplants during a period of rapid inflation, increased total costs in all areas of transplant care are to be expected.

26. The Markup

Surgeon Seth Karp said: “You’re reforming an organ allocation policy so that it rewards the wealthy areas and wealthy states by providing resources from poor areas of the country.”

UNOS

The OPTN’s only interest in developing the liver policy was to save the most lives through liver transplantation while complying with the OPTN Final Rule. To that end, the policy deliberately does not “reward” any area of the country or “punish” any area, nor does the policy assume that everyone in one area is wealthy and everyone in another area is poor. Instead, the policy focuses on individual patients who are on the transplant waiting list rather than on geography. It seeks to ensure the sickest patients get transplanted first – regardless of where they live. It is succeeding by this measure and by other key measures as listed in the two-year monitoring report:

- Liver transplant rates increased significantly for the most medically urgent candidates (those with a MELD or PELD score of 29 and higher, as well as Status 1A and 1B candidates). This was an outcome specifically intended and expected.

- Waiting list removals either for “patient death” or “patient too sick to transplant” decreased by 225 – again a result consciously intended and expected.

- Deceased donor liver transplants increased by more than four percent nationwide in the first two years of the acuity circles policy

Furthermore, the OPTN does not have a financial interest in the outcome of any organ allocation policy changes. The OPTN has no incentive to ensure certain areas receive organs over others; it is charged with creating national organ allocation policies that make the best use of donated organs for the most urgent patients nationwide.

27. The Markup

Kansas patient Gary Gray and his wife ended up going around the transplant system to find a living donor through Facebook due to increased waits. Was this an intended result of the policy?

UNOS

This was neither the result nor the “intended” result of the policy, which, as stated previously, does not exist in a vacuum. Living liver donor transplantation has been performed in the United States since 1989. It has become more common in recent years, particularly since 2016, as transplant professionals have increased their understanding of which patients may best benefit from it, and as they continued to innovate and improve the procedure. Transplant programs use their medical judgment and consult with their patient and a potential living donor to decide whether this is the right option for all.

28. The Markup

Do you believe the acuity circles policy is working? Please explain.

UNOS

It is not a question of belief. The OPTN established broadly-accepted benchmarks for success and we are gratified that the policy is meeting or exceeding outcomes in key areas so soon after implementation. As described earlier, the two-year monitoring report outlines a number of improvements over the previous policy, and generally the outcomes are consistent with high-level modeling results that were considered during policy development.

We will again reiterate that the policy has not been implemented in a vacuum. The sustained increase in organ donation, as well as other advances in medical and surgical care of transplant recipients, also factor into recent system performance. Even so, the acuity circles policy has directed livers more effectively to the most medically urgent candidates, reduced transplant waiting list deaths, and reduced needless variation in different parts of the country for how sick a person must be in order to receive a lifesaving liver transplant.

That said, the OPTN is constantly evaluating and evolving donation and transplant policies and procedures – and at a much faster rate recently than in years past as we take advantage of the exponential pace of innovation in the field. For example: In a few months we will implement a series of changes expected to improve the predictive ability of MELD, PELD, and the 1A and 1B statuses. We are also in the process of developing liver allocation based on the continuous distribution framework, which we expect will further improve transplant equity. The OPTN committees working on these policies and framework are excited about these latest evolutions and we would be happy to share their insights with you.

Go to our responses on the policy’s development. Return to the letter we sent with our responses.